Is Namibia Africa’s next tourism success story? The World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) certainly thinks so, ranking it number one in terms of expected growth in sub-Saharan Africa. Some achievement for a country that was one of the last to gain its independence (from South Africa in 1990) and where tourism only achieved real government recognition quite recently.

And according to research undertaken by the World Economic Forum and the WTTC in 2009, Namibia scores 82nd out of 133 countries in terms of its tourism competitiveness, bettered in sub-Saharan Africa only by Mauritius (40th), South Africa (61st) and Botswana (79th). Namibia scored better than two of its prime competitors in Africa, Kenya (97th) and Tanzania (98th).

It’s an extraordinary country, offering an incredible mix of experiences to the visitor. Most famous for the Skeleton Coast, where the Atlantic beaches rise to the highest sand dunes in the world, Swakopmund is now regarded as one of the extreme sports capitals of the world, with water, air and sand adventures of all sorts available. Namibia also has the Etosha National Park in the north, where the Etosha Pan, a flat saline desert (“the great white place of dry water”) which gives the park its name attracts abundant game and bird life.

Other, but no lesser attractions include the Fish River Canyon in the south, the Caprivi Strip in the north, and the Kalahari Desert in the east.

Sandwiched between Angola and South Africa, and bordered on the east by Zambia and Botswana, Namibia enjoys demand both from the regional market, as well as from Germany, the former colonial power. The majority of visitors to the country arrive by road – Namibia has one of the best road networks in Africa, with long-distance journeys perfectly acceptable by road as well as by air. The main nationalities are as follows:

| Tourist Arrivals by Nationality | ||

| Namibia (2007) | ||

| Angola | 336,045 | 36.2% |

| South Africa | 250,038 | 26.9% |

| Germany | 80,418 | 8.7% |

| Zambia | 40,709 | 4.4% |

| UK | 28,214 | 3.0% |

| Zimbabwe | 26,764 | 2.9% |

| Botswana | 25,649 | 2.8% |

| USA | 19,342 | 2.1% |

| France | 15,019 | 1.6% |

| Netherlands | 13,282 | 1.4% |

| All Others | 93,434 | 10.1% |

| TOTAL | 928,914 | 100.0% |

| Sources: Namibia Statistical Report, 2007 | ||

Investment is, as is often the case, from the main markets – in Namibia’s case from South Africa and from Germany, as well as from domestic sources. One exception to this is Kuwait-based IFA, who have formed OLIFA, a joint venture with the local company Ohlthaver & List. The joint venture has one operating asset, the 106-room Kempinski Mokuti Lodge in Etosha, and is shortly to start construction on the site of the former Strand Hotel in Swakopmund, a “traditional” seaside resort on the Atlantic coast, almost an exact copy of a North Europe Baltic Sea resort, much loved by the German market. The new 100-room deluxe hotel, intended to be Namibia’s finest, will also be managed by Kempinski, and the project also includes branded hotel residences. Two further projects are planned for Windhoek and the Caprivi Strip.

Windhoek will also see a new 138-room African Pride hotel opening in 2011, joining Protea’s 10 other hotels in Namibia. Note that Protea can normally be relied on to pick winners – other countries where they have multiple outlets outside of South Africa include Tanzania and Nigeria, both with excellent growth prospects. The African Pride will be part of Freedom Plaza, a mixed-use development including also retail, residential, entertainment and office components. Investors in this scheme are South Africa’s Madison Property Fund Managers, Swish Properties and Redefine Income Fund, with local partner United Africa Group. An Arabella hotel is also planned in the same scheme.

South African hotel groups dominate the landscape – apart from Protea, Sun International and Legacy are represented in Windhoek and Swakopmund. But the government is keen to encourage other investors and compared to many other countries has an attractive investment environment characterized by: zero customs

duties on imports from South Africa, low excise duties, relatively low VAT, a relatively stable currency (linked to the rand) and stable political climate. The tax system is conducive to growth through the provision of significant and generous initial capital allowances and accelerated depreciation of assets.

Namibia has a great future as one of Africa’s leading tourism destinations. The government wants to reduce its dependency on primary industries such as mining and agriculture which, although important, are focused on specific areas, and therefore do not create employment throughout the country – which tourism can do. Tourism has had a positive impact on resource conservation and rural development. Some 29 communal conservancies have been established across the country, resulting in enhanced land management while providing tens of thousands of rural Namibians with much needed income.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

I have written in previous editions of Ai Tourism Investor about the inroads that the regional and international chains are making into Africa – companies such as Protea from South Africa, France’s Accor, the Brussels-based Rezidor with their Radisson and Park Inn brands, and Starwood’s Sheraton and Four Points brands. A recent survey undertaken by us shows that the new-project pipelines of these and other chains in Africa have never been bigger – Africa is firmly on their agenda!

And happily, many investors in the hotel industry are also keen to secure the services of these chains, so there are deals to be done. But there seems to be some confusion regarding the business models that these groups adopt when entering African hotel markets – how often have you seen headlines stating that “ABC international hotel chain is building a new hotel in ZYZ city”? A headline which is almost always inaccurate! By and large, the hotel chains do NOT invest in nor build hotels. Of course, there are exceptions to this rule – Southern Sun own hotels in Dar es Salaam and elsewhere, and Rezidor have invested in Bamako and other locations.

Typically, however, the likes of Hilton, Sheraton et al are providers only of management and marketing services. Only? Well, of course, these services are key to any hotel’s success, particularly in Africa’s increasingly competitive markets, as more and more hotels open.

Operation and branding by a hotel management company has a positive impact in a number of areas, including:

These benefits should bring greater sales and profitability, and therefore enhanced asset value.

The cost? In financial terms, the chains are charging fees in the order of 3 to 5 per cent of sales, and 8 to 12 per cent of profit, plus a charge for marketing, and other expenses incurred on behalf of the owner of a hotel. Very often there are also upfront fees for technical design services, and the owner will also be required to provide funds for pre-opening and working capital.

Some owners believe that the financial costs are higher than the benefits received from the management company’s services, but in my experience that is due to one or a combination of other factors, rather than to the actual fees paid e.g. the management company does not properly communicate with the owner, or the owner is not ready to accept the loss of day-to-day control that is a condition of the management agreement.

For an owner wishing to retain control of his asset, and to reduce fees paid to a third party, the options are threefold: manage the hotel himself as an independent unit; obtain a franchise with an international chain; or join a marketing consortium.

Independent, unbranded operation can work well, particularly in a sellers’ market. But in the face of competition from professionally managed and branded hotels, the independent hotel invariably performs less well.

Under a franchise agreement, the international chain provides brand standards and marketing support, whilst the owner undertakes the management himself. The customer will not be aware of the difference between, say, a Holiday Inn managed by the owner of the hotel, or one managed by Holiday Inn themselves. This business model is very common in the USA, but far less so in Africa, mainly due to the lack of management expertise that dogs the industry. To the best of my knowledge, most franchised hotels in sub-Saharan are managed not by individual owners but by the major, experienced players – African Sun manage Holiday Inn hotels in Zimbabwe and Accra, Southern Sun manage InterContinental- and Accor-branded hotels in South Africa, and so on.

Fees for franchise agreements are typically expressed as a percentage (5 to 8 per cent) of rooms revenues only. Lower cost than a management contract, but the owner still needs to provide management to the hotel.

Another model entirely is the marketing consortium (so called because they are a collection of independent hotels, and the organisation is run by its members), typified by such global players as Best Western and Leading Hotels of the World (LHW). These organisations provide marketing services to independent hotels, charging a membership fee, which is typically based on the size of the hotel. Whilst certain quality standards and parameters are imposed by the organisation, the owner is able to operate the hotel independently. Best Western imposes a higher branding requirement than LHW – the “hard” versus the “soft” approach. For boutique hotels, there’s the UK-based Small Luxury Hotels of the World, and for those properties where design is “it”, there’s Design Hotels.

How does an owner decide which business model to adopt? For most hotel owners in Africa, the franchise model is not an option – as noted above, global chains such as Hilton and Sheraton will not franchise to independent hotel owners, particularly those without management experience.

So the question is “to manage or not to manage”? And that choice is very often taken not by the owner, but by the debt and equity providers – a lender wants to know who is going to be there generating the cash flow to repay the debt, and may well make the engagement of a professional, branded management company a condition of that loan. Hotel management is not easy, they are complicated businesses, and having a professional in place, with an established marketing network, is a distinct advantage in competitive markets, and in times of a downturn. For many owners, the cost of engaging an operator is fully justified by the financial and other benefits which accrue.

But the international management companies a re not always the answer, and hotel owners with experience of management can consider the option of a marketing consortium like Best Western, who are, like the international operators, increasingly turning their attention to Africa. We are currently working with Best Western to source independent hotel owners with the right quality of product, and the right mindset, to join the consortium. Best Western and others like them provide marketing services only, with the objective of providing brand recognition to the hotel, and driving business to their members through sales and marketing activities. That leaves the independent hotelier free to manage, in the knowledge that they are “not alone”. In addition to the marketing and other business benefits that the marketing consortia provide, the hotel owner gains from the opportunity to network with like-minded hoteliers – a valuable support network.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

HOTEL FUNDING IN TODAY’S ENVIRONMENT

The causes and impact of the global financial crisis are on everyone’s lips right now, with everyone an instant expert on macro-economic theory all of a sudden. And much has been written about where Africa stands in the rather complicated scheme of things.

The “experts”, real and instant, have good news and bad news. The former is that Africa’s banks are hardly, if at all, exposed to the elaborate, and dangerous, financial instruments that have resulted in big-names crashing and burning, but the latter, the bad news, being that the continent is not immune to the aftermath – the economic slowdown, recession, reduction in credit, reduced tourism flows, and so on. And then there’s the mixed good/bad news, the reduction in oil prices from the crazy highs. For oil producing and exporting countries like Nigeria and Angola, bad news, but for net importers, like Kenya, a welcome easing of pressure on the budget. The economic slowdown in Africa is not all that bad news, with growth forecast by the IMF to slow from around 7 per cent in 2007 to 6 per cent in 2008 and 2009 – rather better than the forecasts of recession in the developed world.

In the hotel industry in Africa, the fact remains that many markets are severely under-hotelled, and entrepreneurs are still seeking finance to build new ones. So how are they to be financed if the “normal” lenders are no longer there to assist?

Well, in reality, international capital flows have been insignificant in funding hotel construction in Africa, apart from that coming from “special” lenders like the International Finance Corporation (IFC), part of the World Bank, South Africa’s Industrial Development Corporation, the US-based ExIm Bank and the Nordic sovereign funds which have grouped together in the Rezidor-led Afrinord vehicle. So most hotel development funding has been locally-sourced, with high interest rates and short tenors one of the main reasons for slow development activity.

One solution to the shortage of traditional debt finance is to change your project from a single-use hotel scheme to a mixed-use development. Some commentators state that, due to a combination of high construction costs and tight credit, it is not possible to make a return on a new full-service hotel project. Whilst I find that extreme, the underlying sentiment has some merit, and I believe that mixed-use schemes, where a hotel is developed on the same site as, or even in the same building as, residential apartments, retail, office and other non-hotel uses, have a considerably greater chance of attracting scarce lending. They provide a more consistent – and bankable – cash

flow, either to reduce the lending risk, or in some cases, to reduce the debt requirement by providing project-generated equity.

This model can apply to urban and resort hotels alike. The development of second homes, either on a whole ownership or fractional title basis, can provide significant levels of equity funding to defray the costs of luxury resorts. This has been undertaken very successfully in established resort destinations such as Mauritius, where the Anahita World Class Sanctuary successfully sold exclusive residences, some with the Four Seasons brand name behind them, to assist in the funding of the resort. Several developers of new and existing resorts are looking to replicate this in Zanzibar.

Urban mixed-use developments have equal or greater opportunities, particularly where there is a need to make a return on very high land prices (prime land in Lagos is currently selling at more than US$2,500 per square metre!). Kingdom Hotels, the Dubai-based hotel owner and developer, is currently constructing the new Mövenpick Hotel in Accra with retail, office and serviced apartment components in the scheme, not just to increase the financial attractiveness of the project, but also to generate greater activity on the site from morning to night, and to generate additional income from the synergies between the individual components.

One place where there are numerous mixed-use developments is the Middle East, particularly in Dubai, where hotels are combined with both leisure (holiday homes) and commercial (office and retail) facilities. I have written before regarding the inflow of Gulf funds to hotel and tourism development in Africa, from Dubai World’s investments in mega-projects in Rwanda, South Africa and other countries, to IFA investing in single assets such as the Fairmont Zanzibar resort.

Look for a combination of Gulf finance and mixed-use developments in Africa’s hotel industry in future.

Finally, local finance will continue to be available for good hotel projects, but from relatively new sources. As Africa’s economies stabilise, alongside more political stability, pension funds and insurance companies are attracting increased contributions, and need to invest in long-term projects, to match their commitments. In Nigeria, we have seen several insurance companies purchasing hotels in order to renovate them and benefit from the uplift in profitability and value that results. So look for new, local sources, who understand and accept the local risks far more than do those troubled, and risk-averse lenders far away.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

Having experienced several years of stagnation, Kenya’s tourism industry was on a veritable bull-run. One million visitors in 2002 increased to an estimated two million in 2007, accompanied by an increase in the length of stay from 8.5 nights to 12.1 nights (2006). And that in turn meant a tripling of earnings, vitally important to the country’s goal of eliminating poverty.

In the late 1980s and early 2000s, Kenya had been bevelled by external shocks – the US Embassy bombing in 1998, the effects of the September 2001 attacks in the USA, and the attacks in Mombasa in late 2002. The country, largely the private sector, did what it could to minimise the effect on the tourism industry, but it was not as effective as it could have been.

And then the boom between 2004 and 2007, with increased government contribution to promoting the country’s tourism product. But in late 2007, Kenya’s international image, and by direct association its tourism industry, was severely damaged, this time by an internal shock, the civil unrest that followed the December elections. Tourist numbers and receipts were down by one third in the first half of 2008, resorts were closing down, staff laid off, and it looked like Kenya had “had it”.

But this time the government led the attack, perhaps learning from the experiences of Egypt, so often affected by both internal and external shocks, and each time bouncing back with a vengeance. Tourism to Egypt was devastated by various terrorist attacks in the 1990s, culminating in the Luxor massacre in 1997 when 58 foreign tourists were killed. But in the relative peace thereafter, the country doubled the number of international visitors, by restoring confidence in the tourism product, with the general public and the travel trade.

Kenya has done the same, with massive efforts by the government to assure the world that the country is safe to visit. The last travel advisory, warning US tourists not to travel to Kenya, was lifted in mid-2008, and the industry is expecting recovery to commence in earnest with the winter season this year. The government has invested in promoting the country – a reported spend of well over US$10 million dollars from government funds, and a further US$10 million from the EU, just on marketing.

And at the same time, the local and global hospitality investment industry is expressing just that confidence that the government is seeking to engender, by announcing new deals in the country – Kingdom are investing in the refurbishment of their five hotels in the country, Radisson SAS are to manage a new luxury hotel under

construction in Nairobi, owned by Elgon Investments, and Kempinski and Accor are known to be eying up the market.

Tourists have, thankfully, short memories. They are receptive to marketing messages extolling the virtues of a destination, even when that destination has been portrayed negatively by the same media as are now pushing its benefits. Kenya has just spent over US$2 million on an advertising campaign on CNN – always the first into trouble spots like……Kenya.

How can investors rake the risk of developing new hotels and other facilities in Kenya, when the troubles at the turn of the year are just a few months old? It is because of that short-term memory, that enables a destination such as Kenya, which offers experiences of great depth and impact, and cannot easily be replicated. And it is because, throughout all the problems of the early part of the year, the Kenyan authorities were able to maintain economic stability, so important to investors – the probable recession that so many forecasters foretold has not come about, and forecasts of economic growth for 2008 range between 4 per cent and 7 per cent – not bad for a country with a 1 per cent decline in the first quarter of the year.

And investors are encouraged also by the realisation that Kenya has a large and growing domestic tourism industry, which is not susceptible to the threats which can so easily damage international tourism. Kenyans are the largest users of hotels in the country by far, and also one of the fastest growing markets, increasing from 800,000 bednights in 2000 to almost 1.4 million in 2006. Whilst international tourists bring much-needed foreign currency, a domestic tourist creates the same number of jobs from his or her overnight stay, and the demand is less seasonal. This strong foundation of domestic tourism can significantly reduce investor’s risk.

Everyone lost money in the first half of the year in Kenya. But tourism is a long-term investment, and it is a fact that challenging times are often good for the industry, forcing a reappraisal of product and marketing strategies, and producing a leaner, fitter set of players, ready for the next race.

Kenya, definitely a tourism investment destination of the future.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

Who would have thought it? The government of Kenya is shaken to its core, the Finance Minister has had to step aside after a vote of no-confidence, a foreign country’s (Libya’s) sovereign fund, is involved in the scandal, and a commission of enquiry has been established, all because of the sale of a hotel. Our industry is not usually the subject of political debate and scandal, but then these are obviously special circumstances.

The hotel in question is the Grand Regency in Nairobi, a 226-room property in the centre of the capital. And the hoo-ha is over two things – first that the way in which the hotel was sold was improper, and second that the amount for which it was sold – KSh2.9 billion – was way below its “real” value. Steering well clear of the first point, I will focus on the second, that of valuation, and try to shed some light on this suddenly controversial subject

Critics of the deal, who seem to have become instant experts on the subject of hotel valuation, have bandied about figures twice or three times that figure as the real “value”, and are therefore claiming that the government has been short-changed. Investors in Africa’s hotel industry need to be mindful of the fact that government-owned hotels – and there are many of them around the continent – are highly visible to the public and to the local politicians, and that their sale can be highly emotive, more so perhaps than assets in other industries. Any price offered for hotels needs to reflect the true value, and to be supportable by the facts.

Let’s look first at the difference between “value” and “worth”. I can value anything I own at whatever price I like, and can be content with my personal delusions, but at the end of the day, the realisable value is only as much as the amount it is worth to someone else, that is, what they are prepared to pay for it. Fairly elementary, no? In the High Street, the shopkeeper prices his goods at a level that people will buy them for – any higher, then they will not sell. Still pretty elementary, I believe.

The difficult part comes when you want to work out what that “sticker price” should be. Well, international hotel valuers – and I count myself as one – mostly use the income capitalisation approach to valuation. What we say is – the value of a hotel is

what a rational buyer is prepared to pay for it, who is buying the hotel to make a return on his investment. That return will be generated by the profit from the hotel’s operations. So what is the earnings capacity of that hotel?

Expert hotel valuers look at the condition of that hotel, the way it is managed, its market positioning and competitive situation, the additional investment required to

sustain or enhance earnings, we make projections of future profitability, and then apply some truly complicated algebra to all that figuring (thank goodness for computers!), to come up with the amount of money that a willing buyer would pay a willing seller in the expectation of making x% return.

I’m not privy to the earnings figures of the Grand Regency Hotel in Nairobi, any more than are the majority of the “instant experts”. But what I can do is look at the figure for what it was reportedly sold, compare it with other hotel transactions, and generally judge it for reasonableness in light of what I know about the Nairobi market. Ksh2.9 billion is about US$46 million, which means about US$200,000 per room – and we look at it per room because it is the sale of rooms to overnight guests that is the primary generator of profits in the hotel. I understand from press reports that the hotel is a bit tired, and needs money spent on it if it is to compete properly with the likes of the (refurbished) InterContinental, the upcoming Radisson SAS and other future competitors. So a new owner may end up spending something like US$250,000 per room by the time they’ve finished.

One thing to note about the African hotel market is that the number of transactions against which to compare this figure – US$250,000 per room – is very small. Hundreds of hotels worth billions of dollars are sold each year in Europe and the USA – the annual number of hotel sales in the whole of sub-Saharan Africa, excluding South Africa, is probably less than twenty. So there isn’t much to compare the sale of the Grand Regency with. But there is one, the sale of the former Lonrho Hotels portfolio in Kenya to Kingdom Holdings. A total of 440 rooms and suites was sold in mid-2005 for an average of less than US$80,000 per room. Even with inflation, that’s less than US$100,000 per room today. This price reflected the earnings potential of the five hotels, the condition of the physical asset and the capital a new owner would be required to inject to achieve that potential. The exact same factors which any rational investor would have taken into account when sizing up the Grand Regency Hotel.

So on the face of it, KSh 2.9 billion looks about right to me. And the implied amount per room – US$427,000! – from the suggested “proper” value of KSh7 billion certainly does not! But we need more information to accurately judge what the hotel is worth, and the moral of this story is that potential investors cannot determine the true value to them without full disclosure. Buyers and sellers beware!

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

How to make a success of hotel investment?

In Djibouti, the 177 room Kempinski Hotel was built in just nine months. In Accra, the 100 room Labadi Beach Hotel took a little longer, all of 10 months, but still a record-breaking length of time, that would be the envy of any developer in the west.

So why is it that so many hotel projects in sub-Saharan Africa take such a long time to become reality, with several years’ delay by no means unusual? Examples include the Holiday Inn in Accra, in its sixth year of construction, the Radisson SAS in Lagos, due to open in November 2004 and still on-site, and the Hilton in Kampala, due to open in 2007 and still some way from completion.

And what could, what should be done by investors to stop such a waste of opportunity happening on their projects?

In my experience, so much can be laid at the door of a lack of planning. I believe it was Conrad Hilton who said that the three main success factors for a hotel are location, location, location. Well, that’s a good soundbite, oft repeated in the industry, and it does have much to say about the operational success of a hotel. But I think it is planning, planning, planning that marks the success or failure of your development project.

Here are the four main areas where, in my experience, proper planning brings success:

Hotels are difficult, hotels are complex, hotels are big projects. Like in any endeavour, from preparing a meal to landing on the moon, a multitude of skills is required, and the secret of success of projects like the Kempinski in Djibouti is to leverage off the skills of the individual team members. Every developer knows they need an architect – but hotels are not big houses, they are far more complicated, and the architect must have previous experience of proper hotel design.

The project needs managing, and the project manager needs to be involved from the very early design stages. Project management is a skill which requires experience, and rarely, in my experience, does the investor or the architect have that skill, leading to some of the serious delays that we see. Do the maths – a year’s delay in opening a 200 room project, because the project is not properly managed, could mean a loss of in excess of US$10 million in revenue [YOU MIGHT WANT TO PUT A BOX IN TO SUPPORT THIS – SEE THE END OF THIS DOCUMENT].

The international hotel chains have years of experience in hotel design, knowing what works and what does not. The basic objectives of a hotel design are: to deliver what the guest wants; to maximise the revenue-generating possibilities of the building; to minimise the non-revenue generating areas, whilst still providing sufficient support space; to minimise operating expenses; and thereby to maximise the return on the owner’s investment.

When an architect puts the bathrooms on the outside wall, instead of the corridor wall, “for ventilation”, or a toilet in the middle of the kitchen “for when the chef gets caught short”, or omits any staff facilities, you can be sure that the experts have rejected such design elements long ago for good reason. Architects who insist on ignoring conventional wisdom are ensuring that your hotel will be obsolete when it opens, hugely vulnerable to competition.

I know of several hotels, including the Radisson SAS in Lagos and Le Meridien in Port Harcourt, where expert design experience was sought only after starting construction, which brought substantial delays in completion, and cost overruns, which could have been avoided.

So the management company, if one is to be engaged, must be on the team from the get-go – there is absolutely no logical reason why their appointment should be delayed.

As difficult as it may be (and it is arguably getting easier, with new sources of debt and equity available) to fund hotel projects, it is even more difficult to raise money for a half-completed hotel. There are dozens of hotels around Africa, possibly hundreds, where the cost of construction has been underestimated, and funds have run out, or where construction has started without all of the funding in place.

Disruption of the construction due to lack of funds leads to demobilisation of the contractor, the loss of skilled workers, additional cost, completion delays, and lost opportunities. All of which could have been “planned-out” of the process by ensuring from the outset that sufficient funds are available.

And finally, I can come back to the issue of location (times 3!). Many investors seem to believe that, because they own a site, it is suitable for hotel development. Well, not necessarily! Selecting the correct site is part of the planning process – just because demand is high today, and land is hard to come by (a feature of many, many markets in Africa), these are not good reasons to go ahead with a hotel development on a secondary site. Markets are never static, changing over time, and a location which will “do” today, because of high demand and lack of customer choice, is likely to be

at a disadvantage in the future when supply: demand imbalances are evened out. Conversely, locations can change – look at the decline (and subsequent slow reawakening) of the centre of Johannesburg, where the city’s main 5 star hotels were once located – but this tends to be in mature markets.

Many of Africa’s hotel markets are experiencing a shortage of supply in the face of high and increasing demand – e.g. Lagos, Accra, Cape Town, Luanda – and as a result entrepreneurs are rushing in to exploit the situation. Those that plan properly from the outset – getting the design right, putting the funding in place and having the right development team on the project – are creating sustainable businesses. Those that fail to plan, plan to fail.

A hotel with 200 rooms, achieving 50% occupancy in its first year of operation, will sell 36,500 roomnights. At an average daily rate of US$200, that’s rooms revenue of US$7.3 million. With other revenues from meals, drinks and other services, that’s at least US$10 million in total revenue.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

Kenya’s government has been brought to a standstill and finance minister Amos Kimunya has been forced to resign at news that Nairobi’s showpiece Grand Regency hotel was secretly sold to the Libyan Arab Africa Investment Company at a vastly undervalued price. The hotel was sold without negotiation for an official figure of KSh 2.9 billion – a fraction of the KSh 6 billion top-price estimate being bandied about in the media, but the price has caused a storm of debate as to whether the sale price was fair and reasonable or a huge undervaluing of the property.

The scandal highlights how key an issue valuation is in hotel investment and ownership – how does one ensure an accurate price for the investment when one wants to buy, and what constitutes a fair valuation? What influences hotel valuation? There are many factors to take into account when valuing hotels from their capitalization rate and their room rates, as well as on both their historical earnings and on their current and future earnings.

Other factors such as the health of the hospitality industry and political and economic prospects impact values. The bidding process is also crucial – the Grand Regency transaction was particularly hit by accusations of a lack of transparent bidding that could have pushed up the value of the hotel.

This article should outline, using case studies to back up each point, as far as possible, what hotel investors should be aware of when buying into or preparing to sell a hotel property. You could start by discussing Africa’s hotel valuation / sale history? Explain some successful sales or nightmare scenarios for the investors that have hit headlines – like the Regency. What has actually happened there – can you give some insight?

What makes a successful valuation, and how advanced is the industry in Africa? What are the key factors to be noted in this equation? What affects valuations? Who should investors go to for this?

You might want to add in something about who hotel buyers and sellers tend to be in Africa – are they governments, local investors, international groups? Where are these trends headed – towards more local investment, or something else? What’s directing the market?

You might also want to talk about the process of pricing and negotiating a sale – like, what makes an ideal buyer or seller, and what does a viable and mutually profitable deal need to have as its elements?

Offer your experience – where have you seen successes happen and why? What tips would you offer for investors looking for valuation?

This gives a public view on the Regency scandal – you maybe know more about it than this? Do you agree with the writer?

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

Oil and diamonds drive Angola’s economy, and both commodities are experiencing high prices, resulting in GDP growth at exceptional levels – some 20 per cent in 2007. And this translates directly into demand for hotels. Luanda is experiencing occupancies above 90 per cent year round, with bookings required weeks in advance – and even paying in advance won’t necessarily guarantee you a room!

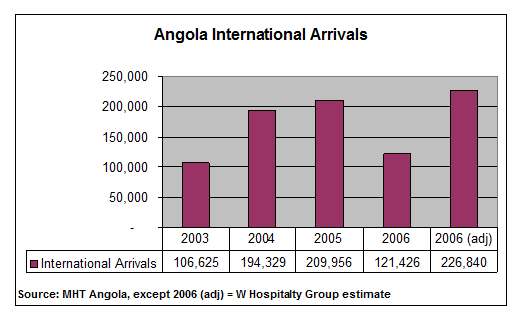

Tourism figures from the Angola authorities are difficult to reconcile with this surge in demand, reporting a decrease in 2006 – but I believe this is due to a change in counting methodology, excluding those coming in for short-term employment from the figures. More likely there is an increase of at least 10 per cent in arrivals year on year, which is the Ministry of Hotels and Tourism’s forecast for the next 5 years, an estimate more than supported by the very high occupancies experienced by hotels in Luanda and elsewhere, and the high load factors of the incoming airlines.

International investment in Angola is growing, mainly for the reconstruction of the country’s infrastructure and in industry. The main investors are the European Union (EU) and the EU countries individually (mainly Portugal), as well as the USA, China and South Africa.

Over 80 per cent of all arrivals to Angola originate from overseas, while 16 per cent originate from within Africa:

| Angola

Region of Origin, 2005 |

||

| Arrivals | ||

| Europe | 110,025 | 52.4% |

| Africa | 45,100 | 21.5% |

| Americas | 36,140 | 17.2% |

| Asia | 16,748 | 8.0% |

| Middle East | 1,243 | 0.6% |

| Australia | 700 | 0.3% |

| Total | 209,956 | 100.0% |

| Source: MHT | ||

Almost 70 per cent of all arrivals originate from seven countries (2005 data not available):

| Angola

Country of Origin, 2006 |

|

| Portugal | 21% |

| Brazil | 9% |

| UK | 9% |

| South Africa | 8% |

| China | 8% |

| France | 8% |

| USA | 6% |

| Total | 69% |

| Source: MHT | |

The majority of visitors to Angola are entering for business and employment, the latter largely in the oil and gas industry:

| Angola

Reason for Entry, 2005 |

|

| Employment | 69% |

| Leisure and VFR* | 15% |

| Business | 13% |

| Transit | 3% |

| Total | 100% |

| Source: MHT

* – Visiting friends and relatives |

|

Angola has considerable leisure tourism potential, but this is unlikely to be exploited for some years, due to the image of the country, the lack of available air capacity and therefore the high airfares, the cost of hotel and hospitality services, the lack of road infrastructure outside of the main cities, and the proliferation of landmines. Many of the leisure visitors are VFR, from the Diaspora in Portugal and Brazil.

The attractions of Angola, which in the future can be exploited for tourism, include:

| · Beaches

· Sport fishing · Game parks · Adventure tourism |

· History and culture

· Natural landscapes · Bird watching · Whale watching. |

The hotels in Luanda accommodate only very small volumes of leisure travellers, and it is not expected that this market sector will grow in the short- to medium-term.

In response to the high demand, several new projects are underway in Luanda – Korea’s Namkwang are building a 250-room InterContinental Hotel, Sivol a 300-room Hotel Sana (a Portuguese operator and investor), and MITC are the developers of a 64-room extended stay property, a product well suited to the type of demand there.

Outside of Luanda, expect more hotel development in Lobito, where a US$3 billion oil refinery is to be built, and in Soyo, where a US$5 billion LNG plant is under construction. In Soyo, a 100-room hotel is to be built by local investor Dania Comercial, and is reportedly already almost fully taken up with demand from the LNG plant. Benguela has tourism potential, with existing beach resorts attracting demand from Luanda at weekends. Cabinda, the enclave within the territory of the Democratic Republic of Congo, is the centre of Angola’s oil industry, and there are plans for massive investment in housing and hotels there.

Such tourism as has been developed is mostly in the south of the country (Namibe Province), with demand generated by the South African and Namibian markets, who drive into the country and visit the game parks and participate in adventure activities in the desert. Road and air access from Luanda has improved recently. The two existing hotels have insufficient capacity for expected growth in demand.

The Angolan authorities are keen to expand the tourism industry, in order to diversify the economy away from primary products, and to take advantage of the country’s natural assets which, due to previous internal problems, have been virtually unexploited. Investment in tourism will bring considerable benefits to the population in rural areas, who see little benefit from the oil industry.

The following data on the number of international arrivals in Angola have been provided by the Ministry of Hotels and Tourism (MHT):

Whilst the reduction in arrivals in 2006 reported by the Ministry is said to be due to a reduction in major conferences compared to 2005, an analysis of the detailed data reveals that the actual reason appears to be a change in methodology of data capture – almost the entire reduction is due to a reduction in the number of migrant workers, a proportion of whom are clearly no longer counted as arrivals. Applying 8 per cent growth to the 2005 figure (2005 was 8 per cent higher than 2004) results in a figure of approximately 227,000 visitors in 2006 (shown above as “2006 adj”), an increase which is conservative and more than supported by the very high occupancies experienced by hotels in Luanda and elsewhere, and the high load factors of the incoming airlines.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

Long-dominated by the luxurious Sheraton Hotel, Addis Ababa is seeing a huge expansion in its hotel stock currently, with at least 1,250 mid-market to upscale new rooms actually under construction, and a further 800 to 1,000 in the planning stages. The Sheraton, and the other branded hotel, the somewhat aged Hilton, are likely to be joined by Holiday Inn, Radisson, Marriott, Ibis, Novotel and Four Points in the very near future.

Driving this boom is a rapid emergence from Ethiopia’s dark years, and particularly greater confidence in the economy on the part of the large and successful Ethiopian Diaspora. Addis Ababa is one of Africa’s primary administrative centres, the home of the African Union and the United Nations’ Economic Commission for Africa. Ethiopia is an attractive country from an investor’s point of view, with its population of 77 million providing an inexpensive, well-educated and trainable labour force. It is strategically located at the crossroads between Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

Agriculture is one of the country’s most promising resources. The potential exists for self-sufficiency in grains and for export development in livestock, vegetables and fruits. Agriculture employs 80 per cent of the work force, and accounts for half of Ethiopia’s GDP and 60 per cent of its exports. Even though most production is at a subsistence level, large parts of commodity exports are provided by the small agricultural cash crop sector. Many other economic activities depend on agriculture, including marketing, processing and exportation.

Ethiopia’s economic growth averaged 8.6 per cent (source: OECD) between 2004 and 2006, driven by agriculture as well as expansion in industry and services. Other sources report economic growth of 10 per cent for the past two years. The World bank is forecasting 9 per cent annual GDP growth to 2010.

Business and conference demand accounts for some 75 per cent of the total demand for hotel accommodation in Addis Ababa and, unlike many African cities which rely almost entirely on the commercial market, the city enjoys a high level of demand from the leisure sector, approximately 16 per cent of total demand.

Ethiopia is shaking off its negative images, and having some success in the specialist leisure market, particularly travellers looking for a unique combination of adventure, history, natural wonder and religion. Addis Ababa boasts several historic sites, such as St Georges Cathedral and the Menelik Mausoleum, but it is in the north and the south of the country that the main attractions lie, including the Northern Circuit, taking in such wonders as the sunken churches at Lalibela, and the Rift Valley to the

south, a birding paradise. With the increase in tourists coming through Addis Ababa, local entrepreneurs such as Tadiwos Belete of Boston Partners, and Sheikh Al Amoudi of Midroc are investing in eco lodges around the country, tapping into their own resources as well as the Diaspora.

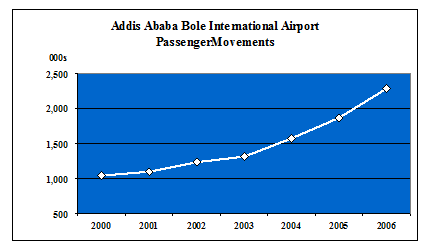

In addition to demand from business and other visitors to the country itself, Addis Ababa’s new airport is attracting increasing numbers of transit passengers, with Ethiopian Airlines having one of the best hubs in Africa. Troubles in neighbouring Kenya, and increasing crime at Johannesburg airport, have heightened the appeal of Addis Ababa as a transit hub. This activity generates considerable demand for hotel accommodation, and Ethiopian Airlines, in partnership with Chinese investors, is planning a new hotel at the airport to accommodate that demand.

Passenger traffic at the airport grew at an average of around 20 per cent in the last three years (2004 to 2006, latest data available), and by 120 per cent since 2000; growth is forecast to be 13 per cent into the near future – Ethiopian Airlines will be the first in Africa to fly the new state-of-the-art Boeing Dreamliner.

For the country as a whole, international arrivals increased by 29 per cent in 2006 to almost 300,000, again more than double the 2000 figure. Preliminary estimates for 2007 are for a significant further increase, due to the celebrations for Ethiopia’s Millennium.

Occupancies in Addis Ababa averaged around 80 per cent in 2007 and, with demand growth forecasts of 8 to 10 per cent annually, much of the future supply should be able to be absorbed without a problem. As is so often found in markets such as this, the internationally-branded hotels will achieve higher occupancies and rates than the locally managed ones, with the exception of the small boutique hotels that find their special market niche. The State-owned Ghion chain of hotels has been the subject of privatisation rumours for many years, and it is hoped that the government’s reluctance to do a deal to date will be overcome as more competition enters the market.

TOURISM AND HOTEL STATISTICS

| International Traffic Movements at Bole

(Arrivals and Departures) |

|||||||

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | |

| Passengers | 1,037,976 | 1,096,605 | 1,237,858 | 1,314,740 | 1,573,330 | 1,869,930 | 2,287,544 |

| Growth (%) | – | 5.6 | 12.8 | 6.2 | 19.6 | 18.8 | 22.3 |

| Source: Ethiopian Airports Enterprise | |||||||

| Addis Ababa

Ethiopian Airlines Scheduled Passenger Movements |

|||||

| Year | Domestic | International | Ethiopian Total | Bole International Total* | Ethiopian Share (%) |

| 2003/04 | 231,797 | 918,067 | 1,149,864 | 1,314,740 | 87.5 |

| 2004/05 | 253,037 | 1,186,754 | 1,439,791 | 1,573,330 | 91.5 |

| 2005/06 | 257,844 | 1,392,409 | 1,650,253 | 1,869,930 | 72.2 |

| 2006/07 | 257,282 | 1,730,932 | 1,988,214 | 2,287,544 | 86.9 |

| Source: Ethiopian Airlines HQ/Ethiopian Airports Enterprise

* Calendar years 2004 to 2006 |

|||||

| Addis Ababa

Transit Passenger Trends 2002 2006 |

|||

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | |

| January | 6,235 | 9,122 | 9,514 |

| February | 4,024 | 6,093 | 5,399 |

| March | 4,188 | 4,201 | 6,272 |

| April | 5,762 | 6,119 | 6,920 |

| May | 6,432 | 5,934 | 6,956 |

| June | 6,184 | 8,022 | 7,780 |

| July | 7,608 | 11,505 | 9,857 |

| August | 7,672 | 11,053 | 10,278 |

| September | 7,145 | 6,678 | 9,951 |

| October | 5,545 | 6,959 | 8,281 |

| November | 5,691 | 7,092 | 7,721 |

| December | 6,052 | 11,252 | 10,591 |

| Total | 72,538 | 94,030 | 99,520 |

| Daily Average | 198.7 | 257.6 | 272.6 |

|

Source: Ethiopian Airlines |

|||

It’s an exciting time to be in Africa, and 2008 is going to be even more fun!

Never before has there been so much interest in the development of new, internationally branded hotels in sub-Saharan Africa, fuelled most recently by an inflow of finance from the Middle East, as investors there seek new destinations to place their petrodollars.

Where are they heading for in 2008? The biggest opportunities in Africa are still for business hotels. Tourism, particularly on the east coast, is booming, but bigger booms are in the oil and mineral capitals in west and central Africa. Granted, there are some high priced safari lodges out there, but the highest rates, and the highest returns to shareholders, are to be found in Lagos, Luanda and other oil and mineral cities.

It is normal in developing countries for the initial focus to be on developing five star hotels, and there are some outstanding properties bearing the Sheraton, Kempinski and other luxury brands to be found, one of the newest being the Kempinski in Djibouti. These brands, and others such as Taj, Hilton, InterContinental, Marriott and Hyatt are all pushing for increased system coverage in Africa.

But I believe that in 2008 we will see increased expansion of midscale hotels, taking advantage of high demand levels whilst at the same time mitigating the effects of rapidly rising construction costs. Like everywhere else, African countries are feeling the effects of rising commodity prices – steel and cement particularly.

Expect more Four Points, Courtyards, Holiday Inns and Novotels to enter, or announce new developments, in the key business markets in 2008. As economies grow, we are seeing increased numbers of regional and domestic travellers, who aspire to the internationally-branded product, but do not have the budget for a five star product. These midscale properties fit the bill perfectly. Four Points are building in Lagos, and Ibis have projects in Addis Ababa and Nouakchott.

Where else are there opportunities for midscale hotels? Business destinations predominate – Luanda, the oil capital of Angola is one, where rooms have to be booked (and paid for) months in advance. Look also at secondary cities such as Soyo, in the north of the country, where a US$5 billion LNG plant is about to “hit town”, creating up to 8,000 construction jobs. A Sofitel has recently opened in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea’s

first branded hotel, and expect to see African Sun following closely behind, in the capital and also in Bata.

Accra is experiencing high occupancies, with increasing room rates. The discovery of oil in Ghana’s Western Region will contribute to further growth in Accra, as well as in Takoradi, the closest city to the oilfields. Golden Tulip are opening in the early part of 2008 in Kumasi, which will put that ancient city firmly on the map, already a major trading and mining centre.

Addis is seeing a building boom, with a joint Novotel/Ibis under construction, and there are plans there for a Marriott, Hilton, InterContinental and, in the midscale, a Holiday Inn. Expect to see new Holiday Inns opening in Arusha, Kano, Accra, Port Harcourt and Dar in 2008, and the reintroduction of the Holiday Inn Express to South Africa, in Cape Town, the first of 25 planned for the country.

Of course there are leisure opportunities in Africa as well, with Zanzibar high on many chains’ lists for development. A new daily flight direct from Addis Ababa further opens up the destination to the main European markets, and Fairmont are at the forefront of brands entering the market. Conferencing is, I believe, an essential element if a leisure destinations is to bring enhanced returns to shareholders, and to mitigate the seasonality and other risks. Destinations such as Ghana’s Cape Coast, Arusha in Tanzania, and southern Mozambique, with good road and air access from major population centres, are therefore prime locations for combined leisure and business resorts.

The UNWTO is forecasting an increase in international arrivals in sub-Saharan African countries of 8 per cent in 2007, way above the world average of 5 per cent, and second only to the Asia Pacific region. Forecasts for 2008 are likely to above this figure, as more hotels open, and more international and regional carriers develop their routes – Delta are making major inroads into the West African transatlantic market, and Kenyan Airways are covering the continent more and more. Domestic airlines are thriving, with new entrants typically creating more demand, which means more opportunities, particularly in the mid market, for the branded operators.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos