Is there an article to be had on the opportunities for local providers to hotels? Interior decorators, IT companies, furniture providers, etc.? Are they competing with international providers? Especially in regards to big chains?

Some 270 hotels with almost 50,000 rooms are in the hotel chains’ development pipelines, as reported in Ai [DATE]. Using an average of say US$200,000 per room to build, that’s US$10 billion of development cost, a significant figure by anyone’s standards!

The trouble is, a large proportion of that sum will be spent outside of Africa. We call it “leakage” in tourism industry parlance, others call it a crying shame, a lost opportunity for Africa. We laud hotels and other tourism establishments for creating jobs, more so in some countries than any other economic activity, but we are typically referring to the jobs in operations, not in the planning and development phase.

Countries like South Africa, Kenya, Egypt and the other “mature” economies are different. They have, to a large extent, the professional skills (architects, engineers etc.), the contractors, the cement and the manufactured products with which to build. And they can deliver the product quality that is demanded by the international hotel chains. Most other countries, including Nigeria, with the largest development pipeline in Africa, cannot.

When developing a hotel at the highest level, say a Four Seasons or St Regis, the owner of the brand will demand that the owner’s professional team is pre-approved by them, often providing a shortlist of architects and others from which the owner must select. This requirement is written in to the signed agreements, as is the brand’s approval of the contractor, and of the products selected. Four Seasons go so far as to insist that they do all the procurement themselves!

Of course, if you want Four Seasons (Hilton, Sheraton, Marriott…..) to manage your hotel, then you must build them a Four Seasons (Hilton……).

Which is perfectly reasonable, any brand in any sector will demand that their specifications are strictly adhered to, whether it is building a hotel, making Coca Cola or producing clothing for Zara.

But whilst the majority of the workforce can be sourced locally, all too often the specialist inputs are just not there. Why should they be?! Why should a country like Ghana, which has built its

wealth since independence mainly on gold and cocoa, and which is experiencing a hotel development boom, have a highly specialised expertise in one sector, just because Four Seasons might come along one day?!

Well, two reasons, first to prevent leakage of millions of dollars of professional fees from their economy, and second to export that skill to other countries in Africa, even beyond.

As in all things, South Africa can be regarded as different, and the expertise for hotel development (and operations) has indeed evolved there, hence the involvement of South African architects, interior designers and others in hotel projects throughout the continent, mostly in the English-speaking countries. But within the rest of Africa, we see very little “cross-border” involvement, so the architects on hotel projects tend to be from South Africa, the UK, the USA and China, instead of from Nigeria, Ghana or Cote d’Ivoire.

Speaking of China, the growing presence of Chinese contractors is very evident, not only because of their competitive pricing, but also because they bring highly attractive financing to projects. But that comes with a cost, further leakage, in terms of the requirement that some 50 per cent of the labour is sourced from China, a morally-questionable demand given the need to create jobs for the rapidly-expanding African workforce.

The solution, in my experience, is professional partnerships, local firms partnering with foreign practices to the benefit of both. The local firm brings its knowledge of the city where the hotel is to be built, including of local planning regulations and relationships with the planning officers. In some jurisdictions, only a locally-registered practice can apply for planning permission, so in those cases it is compulsory for a foreign firm to work with a local practice. And the local firm benefits from the transfer of knowledge, specific to the project as well as global best practice. For the foreign firm, the local knowledge is essential (I have seen designs from foreign architects which are “unbuildable”, because they didn’t seek out the basic information about setbacks, plot density and other requirements), plus the local firm is a source of lower-cost inputs for draughting and the like – and they get a locally-based marketing department, keen to sell their services!

The lack of locally-manufactured products, from cement and steel to furniture and paint, is a more difficult issue to address, in order to reduce leakages. I say “reduce” because it is impossible to source everything in one single country, when a deluxe hotel requires tens of thousands of different inputs.

Nigeria’s Dangote Group is tackling the cement supply, opening factories in several locations around Africa, the latest in Tanzania and Ethiopia. Manufactured, finished products are more difficult, with a lack of electricity and unfavourable exchange rates two of the primary causes of higher prices for locally-sourced goods than for imported ones. Grants are available for the cost of switching to cheaper, renewable sources of energy, and aid funding can sponsor the

development of partnerships between African and non-African firms for the transfer of knowledge to improve the quality of locally-manufactured goods.

None of this is going to solve the problems of sourcing inputs for the development of hotels today, tomorrow or in the near future – but they are (baby) steps in the right direction.

There’s another part to the solution, and that is changing attitudes, be it on the part of the owners, the hotel chains and of the guests themselves.

Is a guest in a hotel in Africa, let’s say in Lagos, so much impressed by the fact that the plate in the restaurant is from a well-known German manufacturer? More impressed than if it was locally-made, or from South Africa? Does the guest even care that much (“I’m not going back to eat there, they have African-made plates!”)? I don’t think “going local” would be such a bad thing, and may even gain kudos for the hotel as guests understand more about the benefits of supporting the local economy.

I know, Nigeria’s manufacturing industry isn’t in any fit state to be producing hotel-quality tableware in large quantities, not yet, anyway. But South Africa does, and Made in Africa is surely a good thing?

Each new hotel development, every refurbishment, brings so many opportunities for local, African suppliers, but with the exception of South Africa and a very few others, I think entrepreneurs are missing a trick, not gearing up to supply the industry with quality products. As countries such as Nigeria and other mono-sectoral economies seek to diversify, it would be great if governments could encourage import-substitution businesses focusing on the quality end of the market.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

Really, when you look at it, nothing much has changed in hotel design since – well, since the introduction of ensuite bathrooms. The Savoy Hotel in London, which opened in 1889 was, the tale goes, the first to have ensuite bathrooms, and the owner, Mr Richard D’Oyly Carte, faced criticism, along the lines of “why the blazes would anyone want a bathroom in their bedroom?”!

In the mid20th Century, the fitness centre entered the scene, with one pioneer in that field, Holiday Inn, dubbing it the “Gym & Tonic”, thereby daring to introduce a bit of fun to the business of hotels which had previously been rather austere and forbidding places.

Rooms have got larger, and have got smaller. 20 years ago Hilton’s standard room size was 32 square metres (including the now-obligatory bathroom), but their standard is now 38 square metres – “by customer demand”. At the other end of the scale, don’t pack that cat when you stay in hotels such as easyHotel in London, or Ibis hotels – there’ll be no swinging tonight, in hotels where the developer’s objective is to fit in as many rooms as possible to the available space. For conversions, such as an easyHotel I once stayed in, that even means no windows in some rooms – and you can pay an extra US$8 or so to reserve a room which does have a window! Well, I’m all for customer choice, but hey! (I paid the extra, and had a tremendous view of next door’s wall – but a window’s a window).

Customer choice, or need, is of course what should always drive design. The brands will tell you that upscale and luxury hotel rooms are getting bigger because that’s what the customer wants. And that in other hotels, they are getting smaller, because customers in those rooms are really only buying sleep and clean water. Exploiting that trend, of the budget traveller who just will not pay for anything else, are the hostel brands such as Generator and Meininger in Europe, and Zostel in India, which are taking the customer back several hundred years to shared bedrooms (but not, as was the norm in the early coaching inn, sharing the actual bed with strangers!).

That fun element I mentioned has become something that is not just a feature, but in some hotels defines the whole concept of the experience. I recently stayed in one of Starwood’s Aloft hotels, where the public areas seemed to be one big party place, with live music in the evenings, piped music everywhere except in the bedroom (peace at last!), and were attracting a young crowd, in-house guests and from outside, as a result. So the facilities in that brand, and several others, are not just there for the in-house guests, but are aimed also at the local community, to get them to spend their leisure time and money in the hotel’s public areas. Hotels such as Aloftdon’t typically (there are exceptions) have restaurants anymore, you go to the pantry, the grab-and-go, then munch and mingle.

In my introduction I said “when you look at it”. The real changes that have taken place in hotel design since Mr Carte’s late 19th Century “revolution” have been behind the scenes, in areas and amenities that the guest never looks at, but certainly feels the impact.

Go into many hotels these days and what’s going on in the lobby (and probably in the bedrooms as well)? People are sitting around, working or playing on their laptops and smart phones, using something that none of us could hardly conceive of 20 years ago – Wi-Fi. Ten years ago it was still a novelty, because we still used plugged-in cables in the rooms, and it was a treat to be able to do that in the public areas as well. Now cables are there, but rarely used (although some companies still forbid their staff from using wireless networks, for security reasons), and we demand wireless, not just any old wireless, it has to be high speed. It is a fact that potential guests, both business and leisure travellers, will choose their hotel on the quality of the wireless connection, and need electrical sockets (which take a variety of plug types) everywhere. This is very often overlooked, so we retreat from the public areas (and stop spending money on food and drinks there) to our rooms, where we have to search under the desk or behind the headboard for a socket. Grrr!

So first it was water, we couldn’t do without it being right there, in our bedroom, for our private use only, and now it is fast wireless internet connection. Hyatt have just announced that wireless internet is to be free in all their hotels, recognising that it is no longer a nice-to-have but now an absolute requirement. Others are highly likely to follow suit, the service being now so far up the hierarchy in customers’ needs, and therefore determining where they spend their dollars. Today we have to be connected, and hotels must fulfil that need.

Another “unseen” advance in design is in the MEP – mechanical, electrical and plumbing. Banging water pipes and radiators, and trickles of brown water from the taps, used to be comic clichés in hotels, but no more – we demand clean hot and cold water, with good pressure, when we want it, now. And air-conditioning (climate control) is more and more a standard feature, to put us more in control of our environment, especially in the bedroom.

What’s happening in hotel design is that, instead of the old “one size fits all” approach, hotels are being designed to meet not just the changing needs of the customer base as a whole – today’s travellers are very different, in so many ways, from those of 50 or 100 years ago – but also aiming their design at specific segments of consumers, Gen X, Gen Y, Millennials, Baby Boomers, Grey Panthers, the lot. So there are those design elements that are common to all. Everyone has an iPad, tablet and/or smart phone these days, don’t they? And everyone wants the other basics to be efficient. Other elements, such as the live music, the absence of a restaurant, the open-plan lobby/bar/lounge/pantry, appeal more to some than others – some guests, like me, still prefer “normal”, walking into a restaurant, that kind of thing. But all, including me, must have excellent Wi-Fi!

Hotel developers and investors who ignore the new basics, and who fail to recognise that different segments want different things, do so at their peril. They are so vulnerable to competition from others who get it right first time. The brands, with their research and development departments, and their sheer scale, have led the way in adapting to those needs, but there is absolutely no reason why an independent hotel cannot do so as well. Let’s face it, we don’t do rocket science in the hotel industry, what we do do is common sense, and that means listening to what our customers want, right from the outset, before any cement is poured.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

trevor.ward@w-hospi

One of the fastest growing sectors of the global tourism industry is that which goes by the acronym of MICE, which stands for Meetings, Incentives, Conferences and Exhibitions. The common denominator is that the events all involve groups of people, sometimes but by no means always travelling together, coming to the same place (destination) with a common purpose.

According to the World Travel & Tourism Council, the travel and tourism industry globally is worth some US$7 trillion. This includes domestic and international travel, for leisure and business, the investment in the sector, spending by tourists and tourist businesses, and so on. It is a measurement of the total industry, which is the most diverse of all.

Of that US$7 trillion, it is estimated that the global MICE industry is worth around US$650 billion to US$700 billion, a sizeable figure. But it is also estimated that Africa accounts for no more than around 2 per cent of that figure, or around US$13 billion. That’s just a quarter of what South Africa spent in the run up to the 2010 FIFA World Cup!

Granted, this is a sector of the travel and tourism industry, like the industry as a whole, that is extremely difficult to measure, or even to define. What constitutes “a meeting”?Or a “conference”? We can all visualise the large events, the International Bar Association, for example, but how can one possibly capture in the data each and every gathering?

The International Congress and Convention Association (ICCA) measures activity in one particular segment of the MICE market, that is the international associations. Each year they produce data on the international meetings of those associations, i.e. the meetings that rotate between different countries. They do not capture the meetings that are always held in the same venue, nor the thousands of domestic meetings that the associations hold each year, the regional chapters and others. Even the ICCA themselves admit that the data they capture, analyse and report on are just “the tip of the iceberg”.

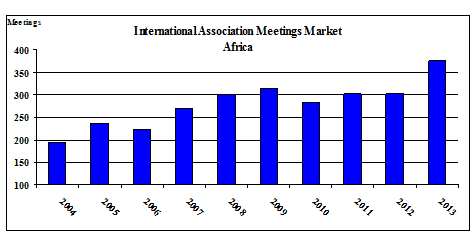

In 2013, a total of 11,685 association meetings were identified by the ICCA to have taken place worldwide, 539 more than in 2012. In 2004 the figure was 7,513, so that market has grown by over 50 per cent in 10 years.

Of the 2013 figure, 375 meetings, just 3.2 per cent of the total, were held in Africa. The fact that that is double the 2004 figure (195 meetings) doesn’t alter the fact that Africa’s share is very low. And of the 2013 figure, almost one third (118 meetings) were held in one country, South Africa. The chart below shows the evolution of the total number of association of meetings in Africa:

Source: ICCA

The top 10 countries in Africa for hosting these meetings were:

| The Association Meeting Market 2013

African Countries Rankings |

||

| Rank | Country | No. of Meetings |

| 1 | South Africa | 118 |

| 2 | Kenya | 38 |

| 3 | Morocco | 30 |

| 4 | Tunisia | 18 |

| 5 | Egypt | 17 |

| Ghana | 17 | |

| 7 | Nigeria | 12 |

| Tanzania | 12 | |

| Uganda | 12 | |

| 10 | Senegal | 10 |

| Source: ICCA | ||

South Africa is ranked number 1 in Africa, and 34th globally. But don’t think “countries”, think “cities” – Cape Town, Nairobi, Marrakesh, Tunis – cities that actively seek to attract these association events, as well as others, for the benefits that they bring to the destination. Such promotional budgets can pass by the man on the street, who sees the adverts for the destination on the sides of the buses, but is not aware of the millions that are often spent by a city on promoting itself as a conference venue.

The large conference market is supply-led to a large extent – whilst organisers may debate where they want to hold their event, the question is also “who can accommodate us”? Who has the conference facilities, the hotel rooms, the attractions and other essential components of the whole? And for the largest events, the destinations will be invited to bid for the right to host the event, sometimes five years before the date.

Why would a city or resort want to attract hordes of people, clogging up the streets and causing annoyance for the citizens? Why would the city authorities spend millions of dollars building a new convention centre, like the Cross River State Government in Nigeria is currently doing (the CICC in Calabar is due to open in early 2015), or extending their existing one (Cape Town), instead of spending the money on schools, hospitals and other social capital?

The answer is that the city benefits enormously from the MICE activity that results, both direct and indirect, and both in economic and less tangible terms.

Informed sources say that the average conference delegate spends six times (six times!) what the average vacationer spends in the destination! Add to that the spend by the organisers on transport, the venue itself, with suppliers in the destination, and that adds up. All that creates jobs, and that’s the direct benefit to the city, and its residents.

What are the more intangible benefits? There are several:

is the medical sciences sector, including the pharmaceutical industry, and these events can be game-changers for developing countries.

In the introduction to the ICCA’s 2011 statistical report, the CEO Martin Sirk states “we struggle to even to begin to comprehend just how powerful international association meetings are as a power for good in the world, let alone calculate and communicate their impact”. The same goes for the entire MICE industry, indeed travel and tourism as a whole. A power for good indeed. Cities in Africa need to wholeheartedly embrace the MICE industry, and focus on it and its benefits (jobs, jobs, jobs!) to their voters.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

Many people know me as being extremely bullish about Africa – after all, I have livedand worked on the continent for almost 12 years, and I have had an involvement in the African hotel industry, particularly in West Africa, for more than 25 years. I have written in this journal for some years now, explaining why the African hotel industry is a “good bet”, and encouraging investors to “jump in”.

I remain optimistic about the prospects for the future in many, many ways, and I intend to stay here for some time to come, but after a year like 2014, I have to confess to tempering my enthusiasm somewhat, and wondering just what 2015 will bring.

It’s all about jobs. Our industry, in its widest sense known as the Travel and Tourism Industry, of which the segment I know best is the hotel industry, is, by some counts, the largest in the world, and is certainly the largest employer of any productive economic activity. And has the potential to generate the most jobs, often in areas where other industries cannot reach, and for unskilled workers, and for women. An industry to be encouraged, and industry to invest in for good returns.

But it is also an industry which is vulnerable to external shocks, such as the re-emergence of the Ebola virus in West Africa in mid-2014, this time with a vengeance. Not just Ebola, but also the terrorist attacks in Kenya, threats in Uganda, rumblings of civil unrest in Mozambique, economic problems in Ghana, and so on. Apart from a temporary influx of aid workers and journalists into affected areas, none of these events are positive for our industry, and all of them result in workers being laid off, and in much slower growth.

The Ebola virus has been the biggest shock in 2014. Ebola has surfaced before, but in relatively isolated areas and never affected “Westerners” before. Between 1976 (when it was first identified) through 2013, the World Health Organization(WHO) reported a total of 1,716 cases – in 2014 there are over 10,000 as of October. The tragedy has most affected three countries, Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, with families destroyed, and the productive capacity of the rest of the population reduced significantly.

According to a World Bank survey of the hotel sector in Freetown[1], hotels are closing, workers laid off, and occupancies in those that remain open are below 20 per cent. Suppliers to the industry are directly affected – the local brewery has put planned

investment on hold and has considered closing altogether – it is estimated that would result in the loss of 24,000 jobs nationwide.

The World Bank uses the term “aversion behaviour” to describe the disproportionate impact of a highly localised event – of the total of over 10,000 cases of Ebola, fewer than 30 have been reported outside the three countries most affected. This aversion behaviour is described as “the root cause of the unfolding slow down”.

Hotel occupancies in Nigeria (20 cases of Ebola, and now declared by the WHO as free of the disease) in July, August and September were close to half what they are normally, the same in Ghana (zero cases). Simply because people were afraid to travel. The Nigerian authorities responded very well, and prevented what could have been a catastrophe if the virus had taken hold in some of the densely populated areas of the country. But international and domestic travellers had no confidence that the authorities could control it, and displayed their aversion behaviour by staying away. Confidence is coming back, at least in Nigeria, but not in all cases – safari operators in Tanzania, deluxe hotels in Cape Town (look at the map for goodness sake!), have experienced cancellations because of what is happening 6,000 kilometres or more away in West Africa.

In East Africa, the resort industry on the Mombasa coastline has also suffered, there due to terrorist attacks, mostly nowhere near where the vast majority of tourists enter the country, and where they stay. Because of governments’ aversion behaviour (issuing travel advisories) and that of tour operators (evacuating their clients from Mombasa) and tourists themselves (switching to other destinations), hotels closed and staff were laid off.

How is our industry going to live up to its reputation for being a champion job creator when we get hit by forces and events which are totally outside our control? Well, I think we will. In our annual Pipeline Report, which provides data on the deals signed by the international hotel chains, we saw an increase of almost 30 per cent in the number of new rooms in the pipeline in sub-Saharan Africa, in hotels due to open in the next three to four years. A very positive metric indeed.

Except that – we are not seeing enough progress to keep up with the opportunity and the need – need not just for hotels to satisfy growing demand, but the need to create jobs. At the recent Africa Hotel Investment Forum (AHIF) held in Addis Ababa, I led a panel of several international and regional operators, and asked them “how many hotels did you open in 2013 and 2014?”. Between the five companies represented, including four very large global players, the answer was, in total, fewer than 10. In 54 countries.

Will we see more hotels opening in 2015? Possibly. No, almost certainly we will, but it’s not enough. In Lagos, the biggest city-economy on the continent, there are only two hotels with an international brand actually under construction, there have been no new starts this year, and only one hotel, the 74-room Lilygate (no brand) has opened. In Abuja, there is nothing under construction with an international brand associated with it.

At that same AHIF panel, I asked the participants what they could do to jolly things along, to move from being “deal signers” to “project creators”. Naturally, the solutions from their point of view are limited – operators’ business model is that they rely on others to build them hotels for them to brand and manage. But we agreed that they need to get much more involved in pushing things along, and if needs be they are going to have to either invest themselves (and we are seeing that happen in a small way), or mobilise finance from other sources, which is the more likely and faster route to progress. Will it make much difference? Well, it is certainly a step in the right direction.

I’m not going to make any predictions for 2015. The world and Africa are going through interesting, nay turbulent times. Did I mention the impact of the slowdown in Europe, virtual stagnation in South Africa, and the energy-self-sufficiency in the USA?! All external factors that can be positive for us – the slowdown in South Africa is leading to investment and professional skills being exported northwards, and the shale gas boom in North America means that our oil industry in Africa must stop being complacent and get out there and sell to other markets.

Here in Lagos, we are seeing a comforting return of international and domestic travellers, and occupancies are on the rise. The prognosis for the future is, as ever, extremely positive – but that’s not a prediction!

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

As far as I can tell, the agreements that owners sign with hotel management companies are unique to our industry. They are frequently misunderstood, not only by those who have no previous knowledge of such agreements, but even by those who sign them!

In a nutshell, the owner of a hotel invests his money to create the physical structure, the building, pays fees to the management company for their advice on the design and the application of brand standards, provides the working capital, and then hands over the property to the management company (also known as “the operator”) to create and build the business. All the risk lies with the owner, and with the lenders to the owner, with zero risk taken by the operator.

On the face of it, that sounds like a one-sided deal, doesn’t it. Well, yes, the agreements are typically very one-sided, some more so than others. What has happened over the years is that the management agreements that each chain signs has evolved – every time an event occurs which the operator believes is detrimental to the smooth running of the hotel, or which has a negative impact on their brand, a clause gets added to the standard agreement template stating that such and such an occurrence would result in the owner being in breach of contract, and is therefore not permitted. The agreements are nearly always originated by the hotel chain, and as time goes by fewer and fewer of the clauses are negotiable – it really does become a take-it-or-leave-it scenario.

The result is an agreement which can come across as extremely arrogant – kind of “build me a hotel to my specifications, then give me the keys, go away and stay away – but be there whenever I need more money”.

Why would any owner agree to such a contract? Well, the answer is quite simple – it is because they cannot manage a hotel as well as the chains can. And why have the hotel chains developed such “aggressive” management agreements? Because what the operator wants is to be left to manage the hotel for the life of the agreement, without interference from the owner, or from third parties. And why don’t the hotel chains invest in the hotels they manage? Because (with some exceptions) that’s not what they do, they manage hotels on behalf of owners who want to benefit from their branding and their expertise and have, historically, had no shortage of owners willing to sign up to that.

I often write and speak about the number of new deals that the hotel chains are signing in Africa – according to our latest pipeline survey, the chains have 215 hotels due to open, the vast majority of which are management agreements. The rest? There

are one or two leases, where the hotel chain pays a rent as if they were leasing a shop, and one or two franchises, where the owner manages the hotel himself, but uses the chain’s brand. Both are still quite rare in Africa, outside of South Africa – the chains want to manage rather than franchise, because then they are in total control, and they don’t like leases, because of the risk and balance sheet impact involved.

One of the features of African hotel development is that a large number of the deals that have been signed are with first-time hotel owners, who therefore have no real experience of how the industry works, and certainly no idea of how hotel chains and their management agreements work. Which is why there can be so much resistance to some of the fundamental terms of contract, such as:

that they have signed a long-term agreement with a particular owner, and there are various parties who, if they became the owner of the hotel, they do not want to do business with (e.g. other brands) and in many cases cannot do business with (e.g. Sanctioned Persons, ex-criminals). We have in most cases been able to remove from the agreement the total veto right of the operator in the event of a planned sale by giving the operator the right to match any offer received for purchase of the hotel, as well as by tightly specifying the classes of prohibited purchaser.

I mentioned above “long-term” agreements. The norm these days is for a management agreement to have a term of 20 or more years with, in some cases, 30 or more. Longer than many a marriage! No wonder they are extremely detailed documents, with the two parties agreeing for an extremely complicated business to be created and run for that length of time in an extremely complicated building. Some management companies I deal with have a set of no fewer than six agreements that an owner must sign – pity the poor hotel consultant that has to read every word of every one, and advise his client!

Seriously though, it is essential for an owner who has little or no prior experience of these agreements to get expert advice – and that means expertise in the hotel industry, and of these types of unique agreement. All too often I deal with lawyers who have never seen a hotel management agreement before, and with gusto try to change every clause, in the mistaken belief that the hotel chains are going to roll over and allow that. It ain’t going to happen, and the relationship will start off on the wrong foot.

Yes, hotel management agreements are one-sided in favour of the operator, but remember that the hotel chains have the same objective as the owner, which is to build a sustainable business over the long term, and to generate superior returns for both parties. To repeat, the management agreements being negotiated in Africa include the self-same structure that works worldwide, and owners should embrace it, from a basis of knowledge and expertise.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

So, does anyone know the answer? Was the FIFA World Cup in South Africa a success, or not?

The world, of course, is divided into optimists and pessimists. The former are either the saviours of the nation, driving forward progress, or naïve and hopelessly foolish Franks. The latter are either never-happy Harrys, or saviours of the nation.

For me, the World Cup, at least off the pitch (they say football is a game for gentlemen, played by thugs – too right!) was a great success. Perfect? Of course not, but there was no racial blood bath, no crime wave to herald the coming of Armageddon, no power cuts – it went well. It proved that, despite the naysayers’ best efforts, that an African nation can organise a world cup event.

As far as the hotel industry is concerned, the results are not unanimously positive, nor are they a disaster. No doubt there will be an inquest into the activities of Match, who certainly appear to have some serious questions to answer regarding the allocations and pricing policies they imposed. But STR Global data for June show that, at least for the hotels in their samples, June was a great month. Cape Town’s occupancy rose 15.9% to 57.8% for the month (compared to 2009), and average rates were up 123.9% to US$258.21. Room occupancies in Johannesburg increased 27.1% to 80.6%, and rates rose 101.9% to US$201.09. Remember, that June is the middle of winter in South Africa, so the World Cup brought an additional high season!

It’s the legacy of the event that needs to be looked at. The pessimists point to the fact that South Africa had other development needs, which were not fulfilled by building football stadia. Yes, probably, but would the money actually have been spent on other, more “socially-minded” projects, had the catalyst of the event not been there? Maybe, maybe not. Is South Africa better off for having hosted the World Cup. Absolutely.

The transport infrastructure has been improved substantially – roads, airports, the new Gautrain link in Johannesburg. The hotel industry has experienced an upgrading that would have taken many years to achieve –if ever – without the push they received. And when South Africa is competing for international tourist arrivals with other countries, the quality of product has to meet and exceed expectations.

Will there be a downturn in occupancies now that the World Cup is over? Yes. It is an experience shared by virtually every other city that has hosted a large sporting event, such as the World Cup and the Olympics. Every city, from Los Angeles and Atlanta to Athens and Madrid, experiences a spike in the supply of rooms, investors building in expectation of the increase in visitors for the event and ever afterwards. History shows that, in most host cities, there is a small reduction in occupancies just before the event (the lull before the storm), an increase in demand and in rates, during the event, and a reduction in occupancies immediately afterwards.

In 2006, when Germany hosted the World Cup, that was certainly the experience – May and August were down on 2005, June saw a major improvement. Data for 2007, the year after, recorded a 3.5% increase in international visitors to Germany, with an 8% increase in holiday trips. Officials use the number of visitors from Brazil as an example of the impact on “new” demand sources – the number of Brazilians visiting Germany was up 74% in 2006, and then down by only 9% in 2007, clearly a legacy of the event in June 2006.

In the run-up to the Beijing Olympics, visitor numbers were down 20 per cent on the previous year, and immediately after the event hotel occupancies crashed from 100 per cent to around 30 per cent. During the event, all but the five star hotels were disappointed by the levels of demand. Why? Because of bad publicity about security and human rights abuses, an “overkill” visa regime, restrictions on domestic travellers, who needed permits to visit Bejing, and a government-driven increase in the number of hotel rooms, accompanied by massive price hikes, resulting in huge oversupply. Not the same as South Africa.

According to the European Tour Operators’ Association “There is no evidence that, post Olympic Games, any city sees a surge in tourism arrivals”. Well, maybe not immediately, but in the long term, the signs are extremely positive. Beijing saw a 50% increase in rooms sold in September 2009, one year after the Olympics. How? By pricing themselves into a recovery. Reports of high prices (in the event, slashed considerably) during the Olympics harmed the industry, and the response was obvious – offer unbeatable prices to demonstrate to the world that Beijing is not as expensive as people thought.

And in Atlanta (Olympics 1996), the development of hospitality facilities was with a clear objective of maintaining and increasing demand levels after the event, by increasing the conference space the city had to offer. Alongside the promotion of Atlanta as a new leisure destination, this opened up new business opportunities for the city.

According to industry observers, the supply of hotel rooms in Cape Town has expanded by 20 per cent in the past 3 years, whilst the figures for Durban and Johannesburg are 36

per cent and 29 per cent respectively. Some will have been encouraged to develop by the forthcoming World Cup, but most will have had their economics based on the general upswing in the tourism industry in the country – which can, if handled properly, only continue once the last goal was scored.

So what’s the future position for South Africa? Well, it still remains to be seen. I have yet to see any follow-up advertisements on CNN or Sky Channel, extolling the virtues of South Africa as a holiday and conference destination. Perhaps they will be on there soon. Because the South African tourist authorities, working together with the private sector – all those people who invested in new and upgraded facilities and services – must get out there and sell, sell, sell. To old markets, new markets, all markets. With very few exceptions, the tourism industry in South Africa emerges from hosting the World Cup covered in glory.

Ride that wave.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

Ghana, one of Africa’s smaller countries, ranked 31st in terms of area and 12th in terms of population, is certainly punching above its weight when it comes to investment in the hotel industry. Unlike many countries, where hotel development is focused almost entirely on the capital city, Ghana is seeing investment in a number of other destinations, as well as in Accra.

It doesn’t seem that long ago that Accra was a sleepy, highly attractive alternative to the noise and chaos of Lagos, and we would visit for the weekend, or extend business trips beyond Friday night, to enjoy the slower pace of life there. Today, Accra’s traffic can be truly “’orrible!”, certainly rivalling anything that Lagos has to offer! And there are construction cranes everywhere, in and adjacent to Airport City, as well as downtown Osu and Ridge, and in the stretch in the middle. Even the beach is seeing residential and other towers going up.

A lot of this is attributed to (or, some would say, blamed on!), Big Oil, which came to town and stayed once the Jubilee Field was proved to be viable. Production commenced in late 2010, and has yet to peak.

But note that Ghana’s economy was growing at between 6 per cent and 8 per cent annually before oil production contributed to a spike of 14 per cent in 2011. In 2008, the last “normal” year before the start of commercial oil production (2009 and 2010 were affected pretty much continent-wide by the global financial crisis), Ghana was in the top 5 of non-oil African countries in terms of GDP growth. Unlike many oil-producers, Ghana has several other viable sources of growth and jobs, including mining (gold), agriculture (cocoa) and services (finance, tourism).

Accra, the political and commercial capital, and the main entry point by air, has seen the majority of investment in new hotels to support, and contribute to, Ghana’s growth, benefiting from the boost from the new oil and gas industry, and from the diversified economy. The latter, particularly an increase in activity in manufacturing and services, is vitally important in order for the hotel sector to thrive and grow.

One of the newest hotels in Accra is the 260-room Mövenpick, which opened in 2011. Owned by Kingdom Hotels Investments, the hotel is on the site of the former Ambassador Hotel, and is the largest hotel in Accra. With two full years of trading under its belt, management have focused on the average daily rate, and whilst its

average occupancy is below the market average, its average room rate is some 20 per cent above its nearest competitor, and its RevPAR is 10 per cent higher.

But the Mövenpick is no longer the newest game in town, that slot was taken by African Sun’s Amber Hotel in Airport City, which opened (finally!) in late 2013. This is one of those rarities in West Africa, a hotel which the operator has leased from the owner. The hotel has sat there, apparently completed, since mid-2012, but with one severe problem – the tenant (African Sun) was, I am reliably informed, not able to finance the purchase of the furniture! Today the hotel is still not entirely open, with only around 100 of the total 200 with beds and curtains!

Future openings in Accra include the 267-room Kempinski Hotel, on the site of the former racecourse, and the 209-room Marriott. Both hotels have been under construction for several years, and although opening of both is slated for 2014, I’ll believe it when I see it! Certainly opening before them is Louvre Hotels 104-room Tulip Inn in South Legon, close to the Accra Mall. This is Royal Airport Hotels’ former Travel Express Hotel, which was sold a while back to raise funds for other projects.

There are several other planned hotels in Accra – I’m aware of potential developers talking to Hilton, Hyatt, Radisson Blu, Park Inn, City Lodge and others, but nothing yet signed. Even Hong Kong-based Shangri La, a deluxe hotel and resort brand, list a potential new hotel in Accra on their web site!

Is there a danger of oversupply? There’s always a danger of oversupply! It happens in any market from time to time, but the likelihood in Accra is, in my opinion low. Look at how long it has taken the Kempinski and the Marriott to – well, not open. Both have been under construction for some years, and this has become established as the norm, not the exception. If both open at the same time, say at the end of 2014, there will be indigestion for a while whilst they are absorbed, but currently there is nothing else under construction of any note, so they and other hotels will benefit from increasing demand (as the economy continues to grow) and as nothing else enters the market. And many would say that the shortage of rooms at certain times of the year means that the city is unable to accommodate the larger conferences and other events which want to hold there.

Royal Airport Hotels were mentioned above as the seller of the Travel Express Hotel – they are also the owner of the highly successful 168-room Holiday Inn in Airport City – surely the only airport hotel ever to turn away aircrew demand because they could fill the hotel with business travellers?! Patrick Fares, owner of Royal Airport Hotels, recognised the potential of Takoradi some years ago and acquired the former Atlantic Hotel there, which he has now renovated and extended to be a 150-room Best Western Plus Hotel, opening this year, and vying to be the first internationally-branded hotel in Ghana’s oil capital with the 100-room Protea Hotel, under construction there.

Takoradi is the centre of the oil and gas industry, Ghana’s “Port Harcourt” so to speak. The port there is one of the centres for the export of cocoa, and there are plans by Chinese construction firm Huasheng Jiangquan Group to invest over US$2 billion to develop an industrial park in Shama, creating some 5,000 jobs. This is part of the Government of Ghana’s drive to develop Takoradi and the Western Region, and follows Lonrho Ports’ announcement of an investment to develop a free port close to Takoradi.

Up in Tamale, in the north of Ghana, Ganaa Hotels Ltd. is currently building a 110-room hotel, due to open this year, and are in advanced discussions for it to be branded as a Best Western Plus, giving the chain a “triangle” of three hotels in the country (Accra, Takoradi and Tamale).

Nothing concrete yet, but investors are known to be looking at Tema, Ghana’s eastern port close to Accra, and at Kumasi. One such investor is the New York and Accra-based BGI, who are primarily planning to develop retail malls, initially in Accra, Tema and Kumasi, and who recognise the synergy between retail and hotels. They are currently seeking brands who will join with them in these developments.

Outside the urban centres, there is interest in resort properties, catering to the leisure and conference markets. The newest opening is the 84-room Royal Senchi Hotel close to Akosombo, close enough to Accra to be easily accessible, but far enough away to generate weekend and other short-break leisure traffic. There is also growing interest in Ghana’s coast, with interest in the Gomoah Fetteh area, where the world-class Whitesands resort is located, and in Ada, where the River Voltga meets the Atlantic Ocean.

Ghana has always been regarded as “Africa-lite”, an attractive destination to do business and for leisure trips. And, despite Accra’s “go-slow” traffic these days, it remains one of Africa’s success stories. I believe we will see new hotel deals signed in 2014, adding to the existing properties, and adding to Ghana’s attractive tourism offer.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

There were several openings of branded hotels in sub-Saharan Africa in 2013, as the previous years’ efforts by the developers, investors and operators to “cover the map” started to come to fruition. Remember that the opening of a hotel is a joint effort – the international and regional chains very rarely put any money on the table, relying on developers and investors to build hotels for them. They, the operators, then provide their management and marketing services to generate profits for the owners of the hotel, in return for a fee.

Openings last year included Best Western in Benin, Kenya and Nigeria, Radisson Blu in Mozambique and South Africa, Kempinski in Kenya, City Lodge in Gaborone, easyHotel in South Africa and, the largest of them all, the Lagos InterContinental in Nigeria. Several others, including the Hilton in Uganda and the Kempinski in Ghana, did not open, delayed again, as are so many hotels in Africa.

At the end of 2013, two of the industry’s global giants announced new deals. Starwood, the owner of the Sheraton, Westin, Four Points and other brands, revealed that they will be managing hotels in Conakry, Nouakchott and Juba, the last-named the first branded hotel in Africa’s newest country, South Sudan. And Hilton announced that they will be managing a 350-room Hilton in Lagos, to be built by Transcorp, the owners of their Abuja hotel.

In the middle of 2013, we saw one of those rare events, a management company investing in a hotel property – Tsogo Sun, owner of the Southern Sun brand, purchased 75% of the shares in the owning company of their Lagos hotel, thus gaining both management and ownership control. The price, US$70 million, appeared “full” at the time, but it included the head lease of a large parcel of land, and the ability to exploit the potential for expansion of the hotel. Not to mention the benefit of gaining control of their own destiny, which itself has a value for a company which desires such control.

Looking forward, whilst I believe that we will still see the single-city deal such as Conakry and Juba appearing on the pipeline analysis, the majority of development is likely to be in 7 or 8 of the 49 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. North Africa is something of an unknown right now, as the region works through the impact of the Arab Spring. But in sub-Saharan Africa, the opportunities are huge, specifically, in my opinion, in Angola, Nigeria, Ghana, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique. That’s seven countries, with some potential also in South Africa, but to a lesser extent due to an already well-developed industry there, and sluggish economic growth.

Of these 7 or 8 countries, Nigeria has the greatest potential of them all.

Why? Because of scale. Take Juba, for example. Quite apart from the tragic civil conflict that erupted in December 2013, the size of the city, and the country, the low economic growth, the mono-sectoral economy and the lack of airlift all point to a hotel market that is likely to be completely satisfied by the planned Sheraton hotel. Of course, there will always be niches to fill, such as the boutique hotel and the economy spaces, but it is difficult to see the city sprouting Hiltons, Holiday Inns, Radisson Blus and the like to compete – it is just not big enough. And once Juba is “full”, where else in the country can developers, investors and operators go?

The same applies to so many other African countries, which have a single city, the capital, and in a few cases another commercial city, where hotels could be developed. But even the capital of several countries has very little airlift to bring in guests for the hotels.

My 7 “picks” are those countries which have the elements necessary for multi-site hotel development – multiple cities with hotel demand, a large(ish) population, a diversified or diversifying economy, higher-than-average economic growth, sufficient and growing airlift into and within the country, and increasing urbanisation.

Nigeria has 36 States, each with a State capital, plus the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) where the country’s capital Abuja is located. In addition, there are some other large urban centres, such as Warri and Eket, that are not State capitals. Many of the State capitals have an airport, with international flights operating to 5 of them. Potentially, therefore, there are 40 or more locations for hotel development, ideal for mid-market brands such as Park Inn, Hilton Garden Inn, Best Western etc. – all three of which already have hotels operating or under development in these secondary cities, with more in planning.

Angola has 18 provinces, also with capital cities, but doesn’t have the scale of Nigeria – around one tenth of the population, for example. The regional and international hotel chains have had very little success with their development ambitions in the country – certainly not for want of trying – and there is still not a single internationally-branded hotel in the country (Sana, a Portugal-based chain, have a hotel there, and also operate in Berlin). Angola is not the easiest place to do business, and developers have preferred to go it alone, with several mid-market hotels locally owned and managed throughout the country. But the potential is there.

Ghana has four or five cities outside Accra, such as Takoradi, Kumasi and Tamale, with Best Western and Protea making inroads into those locations. Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique complete the list, with such developments outside the capitals as Four Seasons in the Serengeti, Serena in Arusha and Zanzibar, Doubletree by Hilton in Zanzibar, and Park Inn by Radisson in Tete.

I remain totally confident about the prospects for the growth of the hotel industry in sub-Saharan Africa. As consultants to the various players in the hotel development process (developers, investors and operators), we are experiencing new highs in the number of enquiries we receive for our services. And these are not all in the “Top 7” – Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Botswana and others are all on the list, and our studies typically identify profitable opportunities to develop new hotels and resorts there.

As markets grow, so do investment opportunities, and whilst the tragic stories from the Central African Republic and South Sudan at the turn of the year suggest that little will happen in our industry there for some time, never say never. Sierra Leone was a failed state not that long ago, whilst currently both Hilton and Radisson Blu have hotels under construction in Freetown.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

Hotels are complicated animals, some developers say they are the most complicated type of building they have come across. And complicated means time and cost, which sometimes mean the same thing. Add in to the mix the need for quality, and you have a threesome that can be very hard to manage!

When we analyse a project, it is always the case that the investment returns are the most sensitive to the development cost, more so than changes in net income, because the time and value of money means that the former, which is incurred now, has a greater value than the income, which occurs much later.

How then, do hotel developers keep costs under control?

From the start of the project, having the right professional team will save the developer money. Just because your architect has designed a good house, doesn’t mean that he can design a hotel. Most hotel guests have no idea what is going on behind the scenes, where up to 40% of the hotel’s area can be located. A poor design takes time to get right, particularly when the architect lacks the knowledge to do so. And the longer things take to do, the later the hotel will open, and that means lost revenue, increased interest charges, and in some cases increased professional costs. One international hotel company will not quote a fee for their technical services (advising on design etc), on the basis that they can only determine how much time they will spend, and therefore the quantum of their fee, until they can assess the quality of the professional team. QCT – Quality, Cost, Time, all closely linked.

If one is engaging an operator, the earlier they are on board the better. The later they come on, the more costly will be the changes that they demand. One developer I know says that bringing on board the operator only after he had started construction cost him US$2 million and two years’ delay! Engaging the operator early on, so that they work hand-in-hand with the architect, will definitely result in cost-savings.

Whilst all members of the professional team are important to the success of the project, one discipline that I always insist must be highly experienced and credible in the hotel industry is the quantity surveyor. Too often I have seen QSs underestimating the cost of a project, either through inexperience, incompetence or simply reporting what the developer wants to hear. The consequence is that there are insufficient funds available to complete the project, which causes delays and claims from the contractor and suppliers, and increases the cost even more. Crazy!

The professional team can, of course, be as expert as anything, but without proper coordination, that counts for little. It is so vital for all the professionals to coordinate their drawings and services with each other to ensure, for example, that the architect provides enough space for the

riser shafts, ceiling voids, services panels, ducts etc.. When the architect is doing his thing in isolation, and the engineers are also working in isolation, then redrafting is required, costing, again, time and money.

Talking of funding, many developers will start construction before securing all of the funding. This is a high risk strategy. If additional debt and equity cannot be raised in time to meet commitments, then the contractor will likely stop work, bringing with it compensation claims and remobilisation costs. And equity investors may well demand a greater share for their money, factoring in the pressure that the developer is under.

Now, I don’t want to be seen contradicting myself, but there will be cases where spending more on the development will save money later on – loading the balance sheet to improve the profit and loss account. Specific examples include using higher quality finishes to save on maintenance and, topically, energy-saving design. A higher quality, more expensive power plant will require less maintenance, fewer repairs and will have a lower running cost, but this also extends to items such as glazing, lighting, heat exchangers, gas turbines, water conservation and recycling, and so on. For projects which embrace a “green” philosophy, the cost of finance can be lowered, using government-sponsored schemes and possibly claiming carbon credits.

For projects in Africa, particularly in the less-developed nations (and it is n countries such as Nigeria, Ghana, Ethiopia and Gabon where the highest number of hotels are under development), we often recommend that a Design and Build Contract is used by developers, to avoid many of the pitfalls that bring unnecessary increases in costs. Design & Build is a traditional form of contract under which the contractor actually does the lion’s share of the design work in-house. This form of contract can only be successfully executed by a large contracting firm that already employs all these skills (architects and engineers) in house. Some contractors claim that they can do Design & Build, but then outsource the work to independent architects and engineers, which defeats one of the objectives which is to achieve seamless cooperation between the professionals. So a developer must verify the contractor’s capability beforehand.

Apart from the benefit of coordination – and that benefit can be considerable as described above – a Design & Build Contract can bring reduced costs in itself. Whilst the contractor will certainly add to the contract sum for the design work, they typically derive their profit from contracting, not design, and as they employ these professionals in house anyway, the additional cost they add to the contract sum is less than the normal percentage one would be paying independents for their professional fees.

Further, if the contractor is in control of the professional team, then he cannot claim from the developer for delays caused by the designers and others! Contractors love variation orders – some say that it is on variations that contractors make most of their profits – and the Design & Build Contract can almost eliminate them from the process.

There are other factors, of course, to consider. Transport costs can add hugely to the development budget, and although sea transport is cheaper than airfreight, the challenge of many

of Africa’s ports (delays, inefficiency and corruption), the condition of the roads, and the delays at land borders, can so delay an opening that airfreight actually works out less expensive.

Import duties vary from country to country, and can change (always upwards!) without warning. Countries such as Nigeria ban some essential inputs for a hotel, such as furniture, so developers must either obtain a waiver, which is not always obtainable, and is not always recognised at the port of entry, or must purchase locally. That would be fine were there a local industry to purchase from, but those manufacturers able to produce sufficient volume at a consistent quality are often fully-booked, and that means higher prices and/or a longer time.

Quality, Cost, Time. An elastic triangle, in which changes to one side will change at least one of the others, if not both. In the hotel industry, never, ever reduce quality – but it doesn’t have to mean increased cost, nor increased time. It all depends on the approach a developer takes to a project, and a determination to do it right first time. We wish!

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

As Africa’s economies grow, the demand for hotel accommodation is also growing apace – in those countries and cities where the main demand is business-related, there is a direct correlation between GDP growth and the increase in demand for hotel rooms. The more diverse the economy, and the greater the share of the tertiary sector in that economy (transportation and distribution, retail, financial services etc), the greater the correlation, and the greater the multiple of GDP growth.

The Africa story is, of course, one of exceptional growth during the past decade, and that’s forecast to continue. So Africa needs new hotels. In years gone by, it was pretty much only government that built new hotels, but now the private sector is making the running. In the ten years that I have lived in Lagos, there has been a sea change in the African hotel industry, made possible by the availability of new sources of finance.

It’s still not easy (will anything in Africa ever be “easy”?!), but we have come along way since the 1980s, when pioneers such as Mr Goodie Ibru, the developer of the Sheraton Hotel in Lagos, were up against all the odds, and more. Goodie received support from the IFC, then pretty much the only international investor in hotels in Africa. It took another 25 years, until 2010 before the next, purpose-built internationally-branded hotel, the Four Points by Sheraton, opened in Lagos, closely followed by the Radisson Blu. Both were funded by local equity investors

What I have seen in the last two to three years is the arrival on the scene – finally – of new, private sector lenders and equity investors. What I call the “special lenders”, such as IFC and Germany’s DEG – “special” because they have a different perspective to risk than “normal” lenders, and because they have a development agenda alongside the commercial return – have been in the market for some time, and are now being joined by others of the same ilk, as well as purely commercial lenders.

One of the largest single hotel transactions in sub-Saharan Africa, the sale of a majority stake in the Southern Sun hotel in Lagos, was closed at the end of June 2013, a US$70 million deal, unique not only because of its size, but also because the buyer, Tsogo Sun, is a hotel operator, and has managed the hotel since its opening in 2009. None of the international brands has expressed any interest in sub-Saharan Africa, seeking instead owners who will engage them to manage their hotels for them. The Southern Sun deal was funded part equity from Tsogo Sun and part debt from a leading South African bank, a “normal” lender.

I wrote about the new and existing funds that are investing in Africa’s hotels in the ^^^^^ issue of Ai – since then I have heard of two international hotel groups who are looking to break the mould and follow Tsogo Sun’s lead, by providing equity to hotel owners, in one case as the majority investor. And then there are other special lenders who are either increasingly active or who are entering the market for the first time. These include South Africa’s IDC, US-based OPIC, and Cairo-based African Export Import Bank (Afreximbank), which seems to have an almost insatiable appetite for hotel investment, so much so that they have developed a special financial product, the ConTour programme, specifically for hotel lending. I was told earlier this year that they have written term sheets for more than US$1 billion of hotel lending. Match that!

Well, others are in there too. I have heard of at least four international construction companies who are willing to invest in hotel projects, and on one case are acting as developers, buying sites and seeking partners to build hotels. One Europe-based contractor is well on its way to establishing a hotel investment fund, which is attracting interest from Africa-based pension funds and others. When fully leveraged, this fund could have more than US$1 billion to invest.

It never is going to be easy to fund hotels in Africa – indeed, they’re difficult projects to fund in many more-developed places as well – but the options are now there, and we’re in a very different funding environment today from what I encountered when I first moved to Africa in 2003, very different and much, much more positive for the future of the African hotel industry.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos