One of the fastest growing sectors of the global tourism industry is that which goes by the acronym of MICE, which stands for Meetings, Incentives, Conferences and Exhibitions. The common denominator is that the events all involve groups of people, sometimes but by no means always travelling together, coming to the same place (destination) with a common purpose.

According to the World Travel & Tourism Council, the travel and tourism industry globally is worth some US$7 trillion. This includes domestic and international travel, for leisure and business, the investment in the sector, spending by tourists and tourist businesses, and so on. It is a measurement of the total industry, which is the most diverse of all.

Of that US$7 trillion, it is estimated that the global MICE industry is worth around US$650 billion to US$700 billion, a sizeable figure. But it is also estimated that Africa accounts for no more than around 2 per cent of that figure, or around US$13 billion. That’s just a quarter of what South Africa spent in the run up to the 2010 FIFA World Cup!

Granted, this is a sector of the travel and tourism industry, like the industry as a whole, that is extremely difficult to measure, or even to define. What constitutes “a meeting”?Or a “conference”? We can all visualise the large events, the International Bar Association, for example, but how can one possibly capture in the data each and every gathering?

The International Congress and Convention Association (ICCA) measures activity in one particular segment of the MICE market, that is the international associations. Each year they produce data on the international meetings of those associations, i.e. the meetings that rotate between different countries. They do not capture the meetings that are always held in the same venue, nor the thousands of domestic meetings that the associations hold each year, the regional chapters and others. Even the ICCA themselves admit that the data they capture, analyse and report on are just “the tip of the iceberg”.

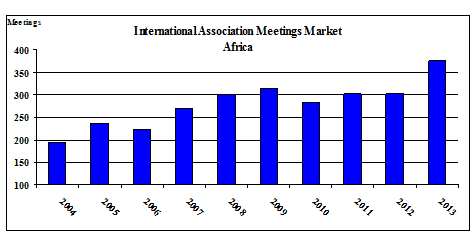

In 2013, a total of 11,685 association meetings were identified by the ICCA to have taken place worldwide, 539 more than in 2012. In 2004 the figure was 7,513, so that market has grown by over 50 per cent in 10 years.

Of the 2013 figure, 375 meetings, just 3.2 per cent of the total, were held in Africa. The fact that that is double the 2004 figure (195 meetings) doesn’t alter the fact that Africa’s share is very low. And of the 2013 figure, almost one third (118 meetings) were held in one country, South Africa. The chart below shows the evolution of the total number of association of meetings in Africa:

Source: ICCA

The top 10 countries in Africa for hosting these meetings were:

| The Association Meeting Market 2013

African Countries Rankings |

||

| Rank | Country | No. of Meetings |

| 1 | South Africa | 118 |

| 2 | Kenya | 38 |

| 3 | Morocco | 30 |

| 4 | Tunisia | 18 |

| 5 | Egypt | 17 |

| Ghana | 17 | |

| 7 | Nigeria | 12 |

| Tanzania | 12 | |

| Uganda | 12 | |

| 10 | Senegal | 10 |

| Source: ICCA | ||

South Africa is ranked number 1 in Africa, and 34th globally. But don’t think “countries”, think “cities” – Cape Town, Nairobi, Marrakesh, Tunis – cities that actively seek to attract these association events, as well as others, for the benefits that they bring to the destination. Such promotional budgets can pass by the man on the street, who sees the adverts for the destination on the sides of the buses, but is not aware of the millions that are often spent by a city on promoting itself as a conference venue.

The large conference market is supply-led to a large extent – whilst organisers may debate where they want to hold their event, the question is also “who can accommodate us”? Who has the conference facilities, the hotel rooms, the attractions and other essential components of the whole? And for the largest events, the destinations will be invited to bid for the right to host the event, sometimes five years before the date.

Why would a city or resort want to attract hordes of people, clogging up the streets and causing annoyance for the citizens? Why would the city authorities spend millions of dollars building a new convention centre, like the Cross River State Government in Nigeria is currently doing (the CICC in Calabar is due to open in early 2015), or extending their existing one (Cape Town), instead of spending the money on schools, hospitals and other social capital?

The answer is that the city benefits enormously from the MICE activity that results, both direct and indirect, and both in economic and less tangible terms.

Informed sources say that the average conference delegate spends six times (six times!) what the average vacationer spends in the destination! Add to that the spend by the organisers on transport, the venue itself, with suppliers in the destination, and that adds up. All that creates jobs, and that’s the direct benefit to the city, and its residents.

What are the more intangible benefits? There are several:

is the medical sciences sector, including the pharmaceutical industry, and these events can be game-changers for developing countries.

In the introduction to the ICCA’s 2011 statistical report, the CEO Martin Sirk states “we struggle to even to begin to comprehend just how powerful international association meetings are as a power for good in the world, let alone calculate and communicate their impact”. The same goes for the entire MICE industry, indeed travel and tourism as a whole. A power for good indeed. Cities in Africa need to wholeheartedly embrace the MICE industry, and focus on it and its benefits (jobs, jobs, jobs!) to their voters.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

There’s a lot happening in Africa!

Earlier this year, a survey by W Hospitality Group counted 215 hotels in the chains’ development pipelines, with almost 40,000 rooms. That’s almost 14 per cent more than in 2013, huge growth in the fastest-growing continent.

Click here to download: 10 Myths of Hospitality Development in Africa

Many people know me as being extremely bullish about Africa – after all, I have livedand worked on the continent for almost 12 years, and I have had an involvement in the African hotel industry, particularly in West Africa, for more than 25 years. I have written in this journal for some years now, explaining why the African hotel industry is a “good bet”, and encouraging investors to “jump in”.

I remain optimistic about the prospects for the future in many, many ways, and I intend to stay here for some time to come, but after a year like 2014, I have to confess to tempering my enthusiasm somewhat, and wondering just what 2015 will bring.

It’s all about jobs. Our industry, in its widest sense known as the Travel and Tourism Industry, of which the segment I know best is the hotel industry, is, by some counts, the largest in the world, and is certainly the largest employer of any productive economic activity. And has the potential to generate the most jobs, often in areas where other industries cannot reach, and for unskilled workers, and for women. An industry to be encouraged, and industry to invest in for good returns.

But it is also an industry which is vulnerable to external shocks, such as the re-emergence of the Ebola virus in West Africa in mid-2014, this time with a vengeance. Not just Ebola, but also the terrorist attacks in Kenya, threats in Uganda, rumblings of civil unrest in Mozambique, economic problems in Ghana, and so on. Apart from a temporary influx of aid workers and journalists into affected areas, none of these events are positive for our industry, and all of them result in workers being laid off, and in much slower growth.

The Ebola virus has been the biggest shock in 2014. Ebola has surfaced before, but in relatively isolated areas and never affected “Westerners” before. Between 1976 (when it was first identified) through 2013, the World Health Organization(WHO) reported a total of 1,716 cases – in 2014 there are over 10,000 as of October. The tragedy has most affected three countries, Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, with families destroyed, and the productive capacity of the rest of the population reduced significantly.

According to a World Bank survey of the hotel sector in Freetown[1], hotels are closing, workers laid off, and occupancies in those that remain open are below 20 per cent. Suppliers to the industry are directly affected – the local brewery has put planned

investment on hold and has considered closing altogether – it is estimated that would result in the loss of 24,000 jobs nationwide.

The World Bank uses the term “aversion behaviour” to describe the disproportionate impact of a highly localised event – of the total of over 10,000 cases of Ebola, fewer than 30 have been reported outside the three countries most affected. This aversion behaviour is described as “the root cause of the unfolding slow down”.

Hotel occupancies in Nigeria (20 cases of Ebola, and now declared by the WHO as free of the disease) in July, August and September were close to half what they are normally, the same in Ghana (zero cases). Simply because people were afraid to travel. The Nigerian authorities responded very well, and prevented what could have been a catastrophe if the virus had taken hold in some of the densely populated areas of the country. But international and domestic travellers had no confidence that the authorities could control it, and displayed their aversion behaviour by staying away. Confidence is coming back, at least in Nigeria, but not in all cases – safari operators in Tanzania, deluxe hotels in Cape Town (look at the map for goodness sake!), have experienced cancellations because of what is happening 6,000 kilometres or more away in West Africa.

In East Africa, the resort industry on the Mombasa coastline has also suffered, there due to terrorist attacks, mostly nowhere near where the vast majority of tourists enter the country, and where they stay. Because of governments’ aversion behaviour (issuing travel advisories) and that of tour operators (evacuating their clients from Mombasa) and tourists themselves (switching to other destinations), hotels closed and staff were laid off.

How is our industry going to live up to its reputation for being a champion job creator when we get hit by forces and events which are totally outside our control? Well, I think we will. In our annual Pipeline Report, which provides data on the deals signed by the international hotel chains, we saw an increase of almost 30 per cent in the number of new rooms in the pipeline in sub-Saharan Africa, in hotels due to open in the next three to four years. A very positive metric indeed.

Except that – we are not seeing enough progress to keep up with the opportunity and the need – need not just for hotels to satisfy growing demand, but the need to create jobs. At the recent Africa Hotel Investment Forum (AHIF) held in Addis Ababa, I led a panel of several international and regional operators, and asked them “how many hotels did you open in 2013 and 2014?”. Between the five companies represented, including four very large global players, the answer was, in total, fewer than 10. In 54 countries.

Will we see more hotels opening in 2015? Possibly. No, almost certainly we will, but it’s not enough. In Lagos, the biggest city-economy on the continent, there are only two hotels with an international brand actually under construction, there have been no new starts this year, and only one hotel, the 74-room Lilygate (no brand) has opened. In Abuja, there is nothing under construction with an international brand associated with it.

At that same AHIF panel, I asked the participants what they could do to jolly things along, to move from being “deal signers” to “project creators”. Naturally, the solutions from their point of view are limited – operators’ business model is that they rely on others to build them hotels for them to brand and manage. But we agreed that they need to get much more involved in pushing things along, and if needs be they are going to have to either invest themselves (and we are seeing that happen in a small way), or mobilise finance from other sources, which is the more likely and faster route to progress. Will it make much difference? Well, it is certainly a step in the right direction.

I’m not going to make any predictions for 2015. The world and Africa are going through interesting, nay turbulent times. Did I mention the impact of the slowdown in Europe, virtual stagnation in South Africa, and the energy-self-sufficiency in the USA?! All external factors that can be positive for us – the slowdown in South Africa is leading to investment and professional skills being exported northwards, and the shale gas boom in North America means that our oil industry in Africa must stop being complacent and get out there and sell to other markets.

Here in Lagos, we are seeing a comforting return of international and domestic travellers, and occupancies are on the rise. The prognosis for the future is, as ever, extremely positive – but that’s not a prediction!

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

There’s only one real news item in West Africa right now, and that’s the impact of the Ebola outbreak. It is a human tragedy, with Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone, fragile post-conflict states before this, now crippled, and with any improvement in their international reputations destroyed. The stigma will remain for some time.

Here in Nigeria, the authorities seem to have tackled the threat really well, with “only” 8 deaths, and no new cases reported for some weeks. Several countries, including Cameroon, Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire have no reported cases.

Whilst the human tragedy is the one to occupy our emotions, there is also a significant impact on our business lives. I wrote last month about the increased hassle in travelling in the region, hassle that has, it seems, successfully halted the spread of Ebola in Nigeria and elsewhere, and is therefore necessary. Even in our daily lives it is impacting, with temperatures checked on entry to my daughter’s school, as well as at bars and some offices.

The problem is that travel, both international and domestic, has been severely affected – international travellers do not want to travel to a region where they might contract the disease, nor do domestic travellers want to be on aeroplanes, confined spaces where they might come into contact with an infected person. Gatherings of people, such as conferences and social events, are being cancelled.

Totally understandable.

But the loss of business at hotels, restaurants, events centres and the like is contributing to the human tragedy. Empty hotels in Freetown and Monrovia cannot pay their staff, who therefore suffer deprivation. The whole value chain suffers, not just directly in the hotels that are laying off staff, but including the loss of revenue at the butcher, the baker and the candlestick maker that supply those hotels, and the staff that work in those allied businesses.

Here in Lagos, the hotels are running at very low occupancies, some below 30 per cent, although their restaurant and bar business seems to be OK. Ebola is only transmitted through contact with bodily fluids, and not through the air, so these places are seen to be “safe”, unlike close contact weddings and other social events.

In Accra too, the hotels are suffering, despite the fact that the country is free from Ebola – the government there announced that they were not hosting any further conferences this year, and the lack of confidence that engendered meant that several events were cancelled, and the hotel industry relies heavily on MICE business.

The Cameroon-Nigeria border is closed completely, and flights between the two countries are not operating. Partial closure of the border is nothing new, dating back several months due to terrorist attacks, but complete closure has meant the stoppage of all trade between the two countries, and the cessation of air services means no travel at all. Again, the knock on effect on the local economies is huge. The Government of Cameroon, who initiated the closure, are giving no information regarding when the border will be reopened, and when flights can resume.

These are difficult times, and whilst we grieve for our cousins in Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone, we are grateful that the authorities in Nigeria and elsewhere have been able to contain the situation – God knows what would have happened had Ebola taken hold in the markets in Alaba, Onitsha or Aba, with shops densely packed together, and thousands of traders visiting daily.

Recovery from the crisis will be all about confidence. The medical authorities will, we pray, announce the end of the outbreak, at some time. But travel, and therefore the hospitality business, is not going to be back where it was until travellers are confident it is safe. We were already seeing signs of nervousness in the first half of the year, when the US issued travel warnings due to terrorist threats. I think “hardened” travellers are less affected by bomb threats and the like, but Ebola? That’s upfront and personal, however careful we might be about where to go and what to do, we could catch it.

Inviting people to travel again after a terrorist attack, once the authorities have given the all-clear, that’s OK. Inviting people back after Ebola will require our guests, and their families, to be absolutely sure they are safe, and that’s a hard call.

Responsible feedback to our guests, based on real evidence, will help to restore their confidence. It is not going to be quick, and here in Nigeria we have the added issue of the forthcoming elections in February 2015 – many might say that they will wait and see what happens then before returning to the country. One hotel general manager told me that October is looking more positive, in terms of bookings, than it has done for a few months – we hope this is the first sign of our recovery.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

A monthly survey of the operating performance of major hotels in the Lagos market shows the average room occupancy for August 2014 at slightly over 40 per cent. This is the lowest monthly rate achieved thus far this year.

[spiderpowa-pdf src=”https://w-hospitalitygroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Impact-of-Ebola-crisis-on-hospitality-and-travel-in-Sub-Saharan-Africa.pdf”]

As far as I can tell, the agreements that owners sign with hotel management companies are unique to our industry. They are frequently misunderstood, not only by those who have no previous knowledge of such agreements, but even by those who sign them!

In a nutshell, the owner of a hotel invests his money to create the physical structure, the building, pays fees to the management company for their advice on the design and the application of brand standards, provides the working capital, and then hands over the property to the management company (also known as “the operator”) to create and build the business. All the risk lies with the owner, and with the lenders to the owner, with zero risk taken by the operator.

On the face of it, that sounds like a one-sided deal, doesn’t it. Well, yes, the agreements are typically very one-sided, some more so than others. What has happened over the years is that the management agreements that each chain signs has evolved – every time an event occurs which the operator believes is detrimental to the smooth running of the hotel, or which has a negative impact on their brand, a clause gets added to the standard agreement template stating that such and such an occurrence would result in the owner being in breach of contract, and is therefore not permitted. The agreements are nearly always originated by the hotel chain, and as time goes by fewer and fewer of the clauses are negotiable – it really does become a take-it-or-leave-it scenario.

The result is an agreement which can come across as extremely arrogant – kind of “build me a hotel to my specifications, then give me the keys, go away and stay away – but be there whenever I need more money”.

Why would any owner agree to such a contract? Well, the answer is quite simple – it is because they cannot manage a hotel as well as the chains can. And why have the hotel chains developed such “aggressive” management agreements? Because what the operator wants is to be left to manage the hotel for the life of the agreement, without interference from the owner, or from third parties. And why don’t the hotel chains invest in the hotels they manage? Because (with some exceptions) that’s not what they do, they manage hotels on behalf of owners who want to benefit from their branding and their expertise and have, historically, had no shortage of owners willing to sign up to that.

I often write and speak about the number of new deals that the hotel chains are signing in Africa – according to our latest pipeline survey, the chains have 215 hotels due to open, the vast majority of which are management agreements. The rest? There

are one or two leases, where the hotel chain pays a rent as if they were leasing a shop, and one or two franchises, where the owner manages the hotel himself, but uses the chain’s brand. Both are still quite rare in Africa, outside of South Africa – the chains want to manage rather than franchise, because then they are in total control, and they don’t like leases, because of the risk and balance sheet impact involved.

One of the features of African hotel development is that a large number of the deals that have been signed are with first-time hotel owners, who therefore have no real experience of how the industry works, and certainly no idea of how hotel chains and their management agreements work. Which is why there can be so much resistance to some of the fundamental terms of contract, such as:

that they have signed a long-term agreement with a particular owner, and there are various parties who, if they became the owner of the hotel, they do not want to do business with (e.g. other brands) and in many cases cannot do business with (e.g. Sanctioned Persons, ex-criminals). We have in most cases been able to remove from the agreement the total veto right of the operator in the event of a planned sale by giving the operator the right to match any offer received for purchase of the hotel, as well as by tightly specifying the classes of prohibited purchaser.

I mentioned above “long-term” agreements. The norm these days is for a management agreement to have a term of 20 or more years with, in some cases, 30 or more. Longer than many a marriage! No wonder they are extremely detailed documents, with the two parties agreeing for an extremely complicated business to be created and run for that length of time in an extremely complicated building. Some management companies I deal with have a set of no fewer than six agreements that an owner must sign – pity the poor hotel consultant that has to read every word of every one, and advise his client!

Seriously though, it is essential for an owner who has little or no prior experience of these agreements to get expert advice – and that means expertise in the hotel industry, and of these types of unique agreement. All too often I deal with lawyers who have never seen a hotel management agreement before, and with gusto try to change every clause, in the mistaken belief that the hotel chains are going to roll over and allow that. It ain’t going to happen, and the relationship will start off on the wrong foot.

Yes, hotel management agreements are one-sided in favour of the operator, but remember that the hotel chains have the same objective as the owner, which is to build a sustainable business over the long term, and to generate superior returns for both parties. To repeat, the management agreements being negotiated in Africa include the self-same structure that works worldwide, and owners should embrace it, from a basis of knowledge and expertise.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

So, does anyone know the answer? Was the FIFA World Cup in South Africa a success, or not?

The world, of course, is divided into optimists and pessimists. The former are either the saviours of the nation, driving forward progress, or naïve and hopelessly foolish Franks. The latter are either never-happy Harrys, or saviours of the nation.

For me, the World Cup, at least off the pitch (they say football is a game for gentlemen, played by thugs – too right!) was a great success. Perfect? Of course not, but there was no racial blood bath, no crime wave to herald the coming of Armageddon, no power cuts – it went well. It proved that, despite the naysayers’ best efforts, that an African nation can organise a world cup event.

As far as the hotel industry is concerned, the results are not unanimously positive, nor are they a disaster. No doubt there will be an inquest into the activities of Match, who certainly appear to have some serious questions to answer regarding the allocations and pricing policies they imposed. But STR Global data for June show that, at least for the hotels in their samples, June was a great month. Cape Town’s occupancy rose 15.9% to 57.8% for the month (compared to 2009), and average rates were up 123.9% to US$258.21. Room occupancies in Johannesburg increased 27.1% to 80.6%, and rates rose 101.9% to US$201.09. Remember, that June is the middle of winter in South Africa, so the World Cup brought an additional high season!

It’s the legacy of the event that needs to be looked at. The pessimists point to the fact that South Africa had other development needs, which were not fulfilled by building football stadia. Yes, probably, but would the money actually have been spent on other, more “socially-minded” projects, had the catalyst of the event not been there? Maybe, maybe not. Is South Africa better off for having hosted the World Cup. Absolutely.

The transport infrastructure has been improved substantially – roads, airports, the new Gautrain link in Johannesburg. The hotel industry has experienced an upgrading that would have taken many years to achieve –if ever – without the push they received. And when South Africa is competing for international tourist arrivals with other countries, the quality of product has to meet and exceed expectations.

Will there be a downturn in occupancies now that the World Cup is over? Yes. It is an experience shared by virtually every other city that has hosted a large sporting event, such as the World Cup and the Olympics. Every city, from Los Angeles and Atlanta to Athens and Madrid, experiences a spike in the supply of rooms, investors building in expectation of the increase in visitors for the event and ever afterwards. History shows that, in most host cities, there is a small reduction in occupancies just before the event (the lull before the storm), an increase in demand and in rates, during the event, and a reduction in occupancies immediately afterwards.

In 2006, when Germany hosted the World Cup, that was certainly the experience – May and August were down on 2005, June saw a major improvement. Data for 2007, the year after, recorded a 3.5% increase in international visitors to Germany, with an 8% increase in holiday trips. Officials use the number of visitors from Brazil as an example of the impact on “new” demand sources – the number of Brazilians visiting Germany was up 74% in 2006, and then down by only 9% in 2007, clearly a legacy of the event in June 2006.

In the run-up to the Beijing Olympics, visitor numbers were down 20 per cent on the previous year, and immediately after the event hotel occupancies crashed from 100 per cent to around 30 per cent. During the event, all but the five star hotels were disappointed by the levels of demand. Why? Because of bad publicity about security and human rights abuses, an “overkill” visa regime, restrictions on domestic travellers, who needed permits to visit Bejing, and a government-driven increase in the number of hotel rooms, accompanied by massive price hikes, resulting in huge oversupply. Not the same as South Africa.

According to the European Tour Operators’ Association “There is no evidence that, post Olympic Games, any city sees a surge in tourism arrivals”. Well, maybe not immediately, but in the long term, the signs are extremely positive. Beijing saw a 50% increase in rooms sold in September 2009, one year after the Olympics. How? By pricing themselves into a recovery. Reports of high prices (in the event, slashed considerably) during the Olympics harmed the industry, and the response was obvious – offer unbeatable prices to demonstrate to the world that Beijing is not as expensive as people thought.

And in Atlanta (Olympics 1996), the development of hospitality facilities was with a clear objective of maintaining and increasing demand levels after the event, by increasing the conference space the city had to offer. Alongside the promotion of Atlanta as a new leisure destination, this opened up new business opportunities for the city.

According to industry observers, the supply of hotel rooms in Cape Town has expanded by 20 per cent in the past 3 years, whilst the figures for Durban and Johannesburg are 36

per cent and 29 per cent respectively. Some will have been encouraged to develop by the forthcoming World Cup, but most will have had their economics based on the general upswing in the tourism industry in the country – which can, if handled properly, only continue once the last goal was scored.

So what’s the future position for South Africa? Well, it still remains to be seen. I have yet to see any follow-up advertisements on CNN or Sky Channel, extolling the virtues of South Africa as a holiday and conference destination. Perhaps they will be on there soon. Because the South African tourist authorities, working together with the private sector – all those people who invested in new and upgraded facilities and services – must get out there and sell, sell, sell. To old markets, new markets, all markets. With very few exceptions, the tourism industry in South Africa emerges from hosting the World Cup covered in glory.

Ride that wave.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

West Africa is still only a relatively small player in the international meetings market (and Africa as a whole has just a 4 per cent share of the international association market), although various venues have had success in the regional and domestic market. One is Dakar, which has been a favoured conference destination for many years, particularly with Francophone countries.

Dakar has good air connections to Europe and some good quality and professionally-managed venues. Large-scale purpose-built venues are to be found in Accra, Cotonou, and throughout Nigeria. Dubbed the “Conference Capital” in the country’s Tourism Master Plan, Abuja has several large venues, in the Hilton and Sheraton hotels, and in the non-hotel, stand-alone International Conference Centre and the ECOWAS Centre.

But the largest of these is “only” 2,000 seats, nothing compared to the Expo Centre in Lagos, and some of the planned venues in various State capitals around the country. Cross River State Government recently launched the Calabar International Convention Centre (CICC) – for those with a quirky sense of humour, it is amusing that the launch took place at the Cape Town International Convention Centre, Africa’s leading venue! A government-led initiative, the CICC is part of the State’s objective of generating more revenue internally (and thus lessening the dependence on central government hand-outs), and to reap the benefits that a large-scale venue can bring – jobs, jobs and more jobs. Creating jobs increases social harmony, reduces the burden on the State, and spending by the newly-employed boosts other sectors of the economy. The extended families that job-holders support benefit too – better nutrition, less sickness, and educated children.

The total capacity of the CICC is 5,000 persons in 21 different halls, and the State government is already taking bookings for the expected opening date of February 2015 – construction started in 2012, the project is on track for partial-completion by the end of 2014.

In the emerging economies of West Africa, there is a greater need than ever for Africans to meet and to share experiences, learn from each other and make plans for the future. This correspondent believes that the meetings industry – the real one, not the virtual one – has a very, very bright future.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

International travellers to Nigeria often return home with their “war stories” regarding the urban jungle of Lagos, the lack of infrastructure and the chaos on the roads – chaos, by the way, that we learn to live with (but never get used to!), and which we call home.

It amused me recently to read online an interview with a Swedish visitor, who had been to Nigeria, and said she couldn’t understand what the fuss was about, she had found a modern, clean city with super highways, traffic lights that work, and a definite absence of chaos. She was returning home with a very positive view of Nigeria.

She had, you might have guessed, visited Abuja – only!

The capital of Nigeria is a very different city compared to the rest of the country. Lagos was the original capital of modern Nigeria, but the city couldn’t cope with the pressure on its infrastructure and this, plus political considerations, led to the decision in the early-1970s to establish a new capital in the centre of the country. Construction commenced in the late-1970s, and the capital officially moved to its new location in December 1991.

At the time of the city’s inauguration, two huge hotels were operating, both owned by the Federal Government – the 670-room Hilton, and the 540-room Sheraton, two of the largest hotels in the whole of Africa. A third, the 580-room Abuja International Hotel, was completed in 1990, but didn’t open until 2003, with less than half the rooms available. The hotel trades today as the NICON Luxury Hotel (yes, that’s what they call themselves!), and the remaining rooms have never been completed.

Other branded hotels in Abuja are three by Protea, and a Hawthorne Suites. Just six branded hotels in the capital of Africa’s largest nation.

And, strangely enough, there is very little activity in the branded hotel sector. Abuja has many hotels, ranging from small boutique hotels to large hotels such as the NICON and the Bolingo. Travel around the streets of Abuja, particularly in the districts to the west of the CBD, and you will see many hotels under construction which have been abandoned – the owners had some money, underestimated the amount required to complete a hotel, started building and, well, stopped.

But as I write there is nothing under construction that is to be internationally-branded. Strange, huh? Some deals have been signed – Marriott have a project for a Courtyard and a Marriott Executive Apartments, and Carlson Rezidor have signed both a Radisson Blu and a Park Inn. But none of these is yet on site.

The hotel industry in Abuja has suffered some serious setbacks in the last three of four years, having been a target for Boko Haram attacks and threats. Most serious have been the bombings at the UN headquarters, retail malls and bus stations. Threats against the main “American” hotels have had less physical impact, but have also served to dampen demand. Some companies and agencies forbid all travel to the city, and several international conferences, with the notable exception of the World Economic Forum earlier this year, have been “pulled”.

But there have been other impacts on demand – in 2012 and 2013 there were continuous decreases in the number of airlines operating in between Lagos and Abuja, for various reasons – at the beginning of 2013 the number of airlines on the route reduced from six to just two, and one of those stopped flying for a few weeks as a result of a labour dispute

For the future, I am very bullish about Abuja. Not only is it the nation’s capital, it is also where the nation’s purse sits, and it is necessary for both private and public sector to go there for funds, on a regular basis. It is, since earlier this year, the capital of the largest economy in Africa, and people are waking up to that – “we must be there”. The airport is experiencing high growth, with new airlines commencing services each year – Kenyan have started on the Nairobi route this year, to be joined shortly by Emirates, Turkish and Rwandair. SAA also have rights to fly to Abuja from Johannesburg.

So long as the terrorist attacks in Abuja continue, demand will be depressed, but we must believe that they will cease, hopefully soon. Meanwhile, many of our clients are considering hotel development in the capital, and the traveller can look forward not only to a modern city, but one with modern hotels in all categories – not only are many of the deluxe chains looking to establish a presence in Abuja, but so too are those operating at the budget and midscale level.

We just need to encourage some of these projects to get moving. Watch this space!

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos

Travel used to be really exciting, didn’t it? Especially travel by air – going to the airport, seeing all those planes, boarding and taking off,heading for pastures new. Even travelling around Africa could be fun, with travellers’ tales abounding about how awful this and that airport is,which side of the aircraft to sit to see Kilimanjaro, and tips on what to do and to avoid.

Today, travel is a real chore, in some cases downright unpleasant until you get to cruising altitude at 30,000 feet. We have to get to the airport earlier and earlier, because of the security checks (granted, we can check in on-line, but at many airports I go through, I still have to go through “normal” check-in, where they tear up the boarding card you printed, and give you a new one).

Before check-in, there’s a machine for your bags to get through the terminal doors, two or three people to look at your passport, another two to look in our luggage (guys, if you’re going to do it, do it properly, lifting the corner of a shirt or two isn’t security). At passport control, you might have three or four people looking at your passport. Currency control, food & drugs control, Uncle Tom Cobbley and all. At the gate, more baggage screening (desultory shirt lifting), more passport checking. Then there’s the personal screening, laptop, belt, shoes, fluids, jackets, phones etc., hardly ever the same requirements from one place to another.

All done with a snarl. When they say “You’re welcome”, it certainly isn’t sincerely meant!

And now, there are the health checks, due to the Ebola crisis. In Lagos, there’s one by the Ministry of Health before you check in, another right next to that done by the airline, and a third, byt the Ministry of Health again at passport control. There’s a form to fill in, about who I am, how I feel, and where I’ve been recently. The form says “have you been to Sierra Leone, Guinea, Liberia or Nigeria”? So on arrival in Kigali (note that I had filled one in at the airport in Lagos), I tick yes to Nigeria, that’s where I live, and that’s where the fight came from. The health official was shaken. “You’ve ticked yes? You’ve been in Nigeria?”. Well yes, that’s where the flight came from, I live there, is there a problem? The thing is he couldn’t work out whether that was a problem or not! He hadn’t been told what to do if someone ticked “yes”. In the end I was allowed through, having had my temperature taken again – I was so worried that I wasn’t going to be allowed in that my temperature must have been going off the scale!

My point here is that everything I encounter at airports is so disjointed, and unnecessary. “Unnecessary?!” you exclaim indignantly. Of course I don’t mean that airports shouldn’t have security, shouldn’t be checking for Ebola, I want to be secure when I fly (which I do virtually every week of the year), and I fully understand the terrors of spreading Ebola – it scares the hell out of me. But why do they need to take my temperature three times within the space of ten minutes? Why do 12 people (yes, 12!) feel the need to check my passport when I am leaving Lagos? In most airports, including most in Africa, it’s just three people – check-in, passport control and boarding.

The reason for this “multiplication” of security is that no-one trusts anyone else, the different agencies are just not joined-up in any way. No-one is coordinating the physical security of travel, and now the Ebola screening, there is no co-ordination. There is no sense of treating travellers as guests to be welcomed, and hope to see you again. For a visitor, it generates feelings of anxiety and animosity, and not particularly wanting to repeat the experience. That’s bad for business.

Talking of which, the Ebola crisis in West Africa is seriously impacting the travel and tourism business. In Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, where the outbreak is at its most serious, there is no business for the hotels. In Lagos, where Ebola has not taken hold, the hotels are running at 30 to 40 percent below what they expected at this time of year, the schools have been closed until mid-October, and the event centres are empty. People don’t want to take the risk of going to places where they might contract the disease, and that means fewer international travellers, cancellations of social events, folks are staying at home.

It’s not just West Africa, I have been travelling in East Africa, and I have heard of cases of American and Chinese tourists cancelling trips to Tanzania, for fear of Ebola. This fear is such a personal thing, you can’t say “look at the map, will you?”, if they’re scared, they’re scared, and let’s be honest, it could happen.

So as well as the human tragedy, there is the impact on the business world, and thatlinks back into the populace, as workers have reduced wages, or are laid off.

If people are afraid of travelling, and going to restaurants and events, there is little the hospitality industry can do about it. We pray for a speedy end to the Ebola crisis, and for those directly affected by it.

Trevor Ward

W Hospitality Group, Lagos